|

I wrote this 10 years ago about a little girl I knew at a pretty awful school. I recently read an essay written by this child, now an adult. I was so inspired to see how the genuineness of the human spirit endures and transcends. Caroline MacCreedy. Not even ten years old, four months shy.

The things she likes: Bugs, any variety. She likes to tell people that horseflies find sugar with their feet and that ticks can grow from the size of a grain of rice to the size of a marble. One of her favorite facts: wasps that feed on fermented juice have been known to get drunk and pass out. "oh shut your pie hole!" her mother sometimes says. "Holy Crap. I am sick of bugs." Caroline. 4'5" straight dark hair bangs that just touch the top of her eyebrows. At school, for two years -since second grade-- the mean girl Marla makes all the other girls ignore her. Finally, this year, Caroline says "I don't care about you" She pretends to bite them. When she does, Marla rolls her eyes and laughs right in the Caroline's face. "You dress like a baby." Ya. Ya. Ya. Caroline's mother tells Marla's mother, "your daughter is bullying my daughter." Marla's mother says "Everyone knows Caroline has problems with her attitude. She's a hard kid....It isn't easy for the other girls to like her. Marla tries to be nice." Caroline finds if she walks around the playground imagining species of bugs and their characteristics, the other kids can't hurt her. About one-third of all insect species are carnivorous, and most hunt for their food rather than eating decaying meat or dung-Nobody else in this classroom knows that, Caroline thinks. Its late spring, the sun is finally outside when she is out at recess. Walking. Thinking. She imagines a dung beetle on a steaming pile of cow poop. People aren't what they seem, she thinks. The Mexican jumping bean is really a caterpillar. "Asbergers" the teacher posits, "low achiever. Maybe an IEP?" " A diagnosis" her mother says, "If I just had a diagnosis." School is harder now. There are insects in Caroline's brain. They fly around and make her frightened. They aren't really bugs, but Caroline imagines them that way. When it is her turn to talk in class, she looks at the other girls. She feels the slugs in her throat and she can't speak. "I'm never talking to anyone in that class again." She announces at dinner. "Why?" her father asks. "Because I hate it there. People are mean and the work is hard" At school Caroline watches Marla every day and one day walks up to her at lunch and says "Marla you are a knuckle head." Marla says back "you are weird, Caroline. A weirdo." Marla tells all the other girls the new rule is no one can talk to Caroline Mac "Wierdy." When Caroline looks for someone to sit with for reading group, all the girls turn their backs. Marla glares at Caroline, then smiles when the teacher looks over. Caroline starts to cry at night and her mother asks, "What is wrong?" "Marla is my arch enemy" Caroline says. "I'd like to sever her main artery with my teeth." "We don't talk like that in our family." "I need a diagnosis," her mother says on the phone in the morning. At night. In the evening "I don't know maybe Autism? Something has always been wrong. She isn't an easy kid to be around." Caroline sits out in her back yard on the cement step. It is misty and cold and she doesn't care about anything. She has a secret. She is one of the insects. She is an anthropod and the colder it gets the harder the beetle shell around her body gets. Insects have been present for about 350 million years, and humans for only 130,000 years, she thinks to herself. So who cares about Marla? Who cares about people? Caroline will be around a lot longer than them anyway. She picks up a leaf and inspects it. Runs her fingers along its veins. If she were an ant, she could climb its ridges. If she were a fairy fly -the world's smallest insect, so small they are seldom noticed by humans-- she could follow the little lines of the leaf, she could understand that tiny specimen of life. It's translucent green skin; she could suck the nectar from its tender veins. She looks more closely at the back of a leaf. The patterns that she sees are all repeating. It looks like a leaf inside of a leaf inside of a leaf. Caroline imagines that it goes on forever that way. And, she thinks for a minute that maybe that is some kind of portal, a portal into the insect world. If she could keep following it, she could get in. If she were a fairy fly, she'd be small enough to escape. Things are quiet outside, but she can hear the vacuum cleaner running inside of the house. It is the low hum of a cloud of phantom midges over a lake in the summer time. If she closes her eyes she can be there. She thinks of a poem in her mind: This is what you see: a back yard with a broken wheelbarrow in the corner. Trees that provide shade in the rising heat of summer You see the path that leads to the drive way You see the car parked just beyond You see what people see. This is what I see: I see the faint breeze as it barely rustles the trees The waking larvae hiding under a pinecone decomposing and making fresh earth I see the trails that black ants make as they carry fifty times their weight I see the bark and smell its pine scent. I see life all around me. I see what nature sees. ****

0 Comments

The challenge? Presenting a narrative in 15 seconds to one minute.

TikTok is not known for storytelling in the traditional sense. It's a video medium and most often performance based. I wondered what happens to a narrative when it is distilled into small, palatable bites? Would the medium allow me to preserve the integrity of the story in any way? Here are a couple of attempts at sharing my writing on TikTok.

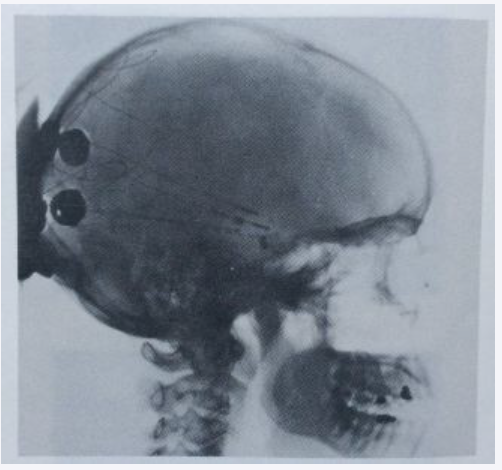

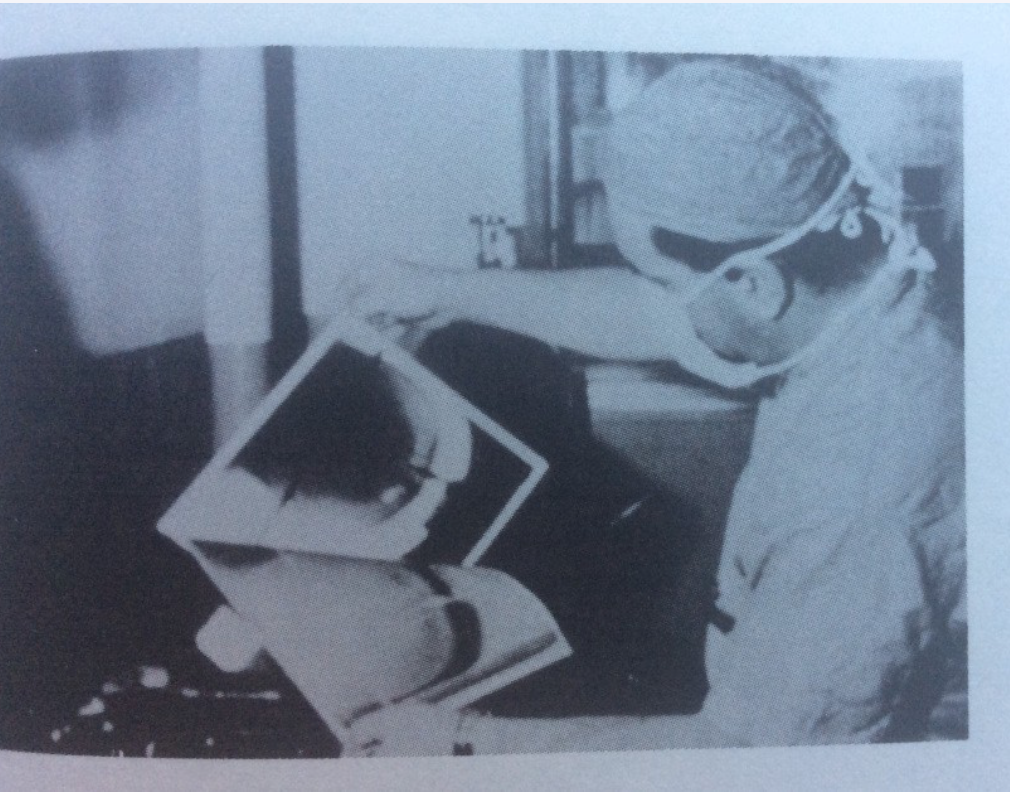

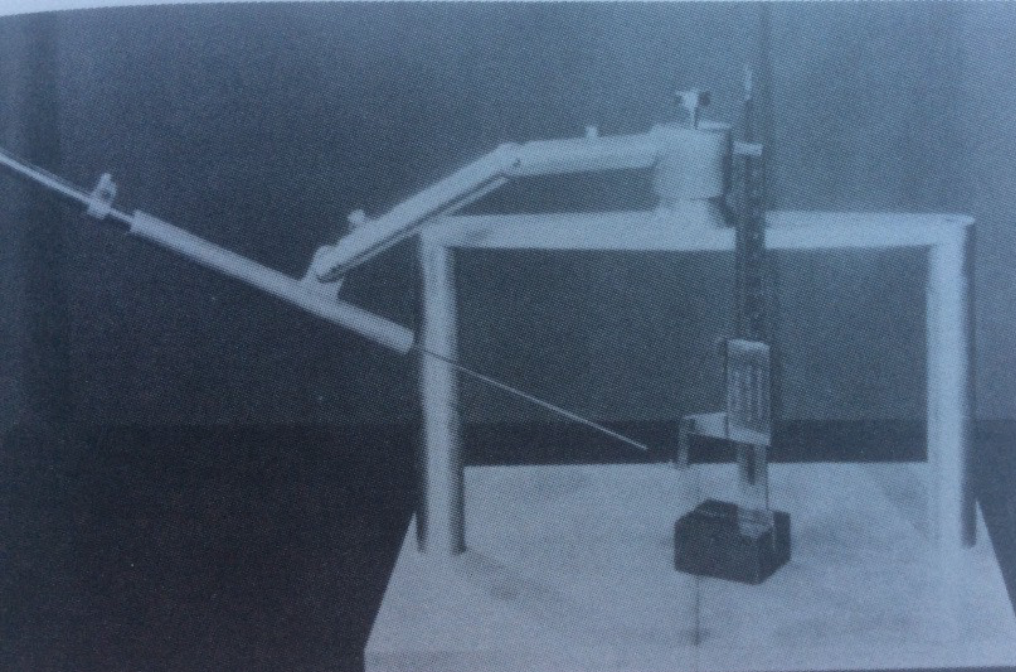

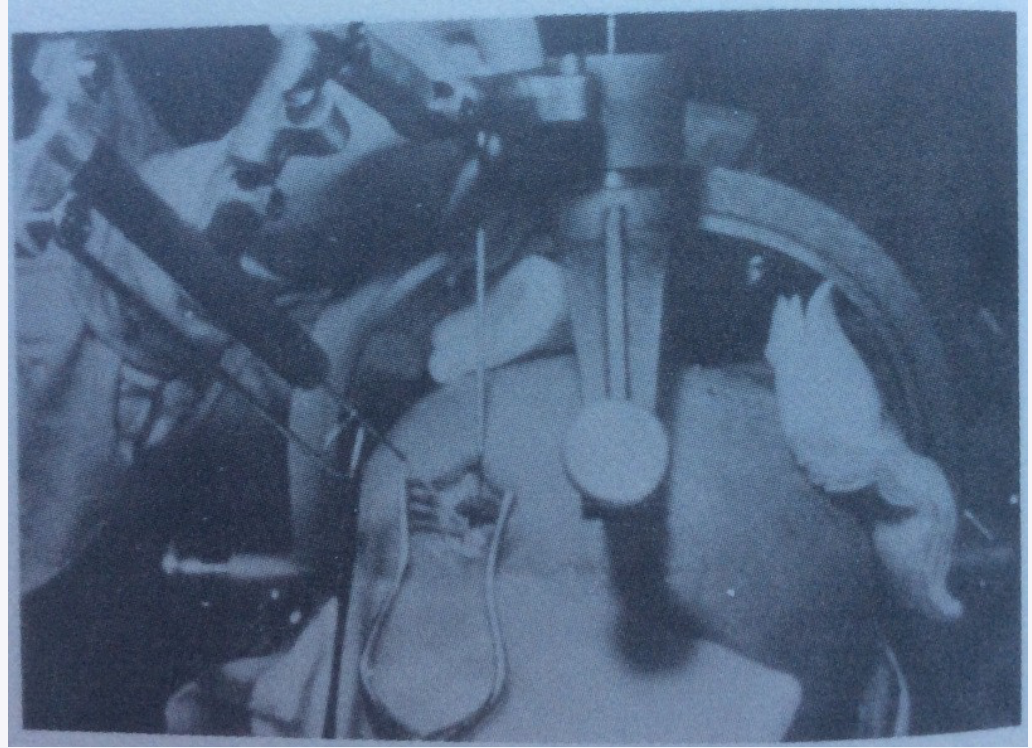

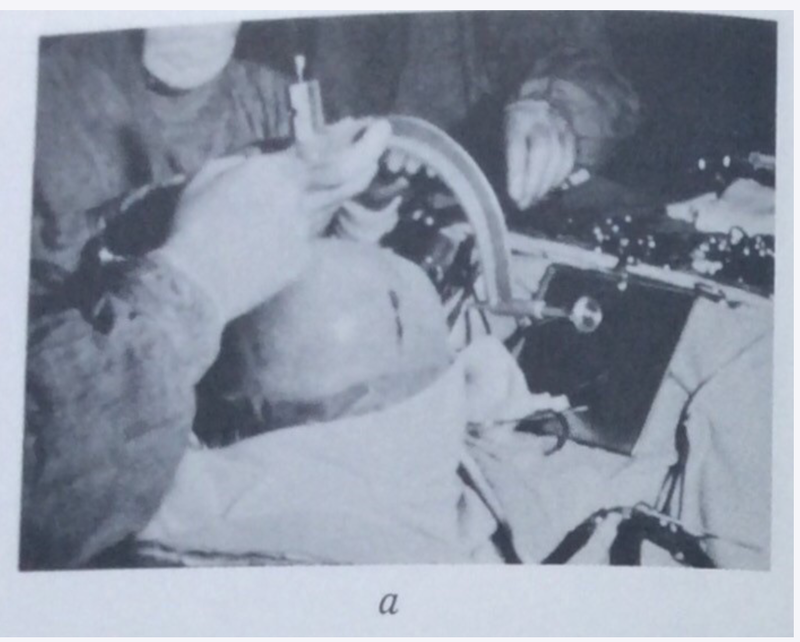

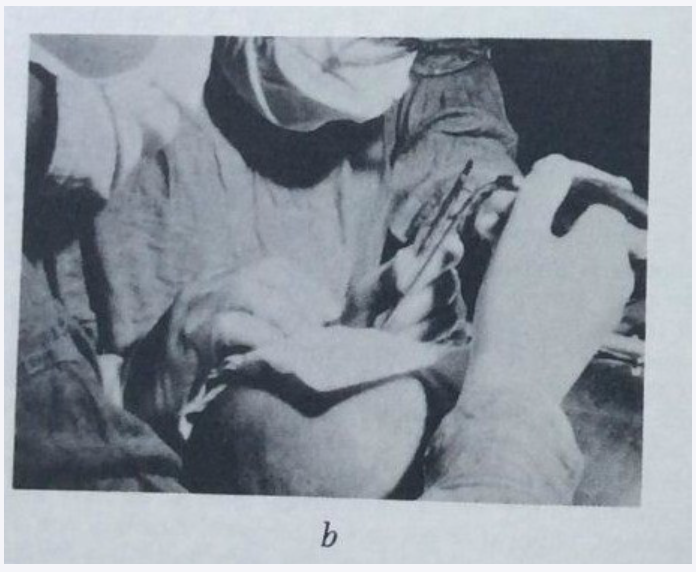

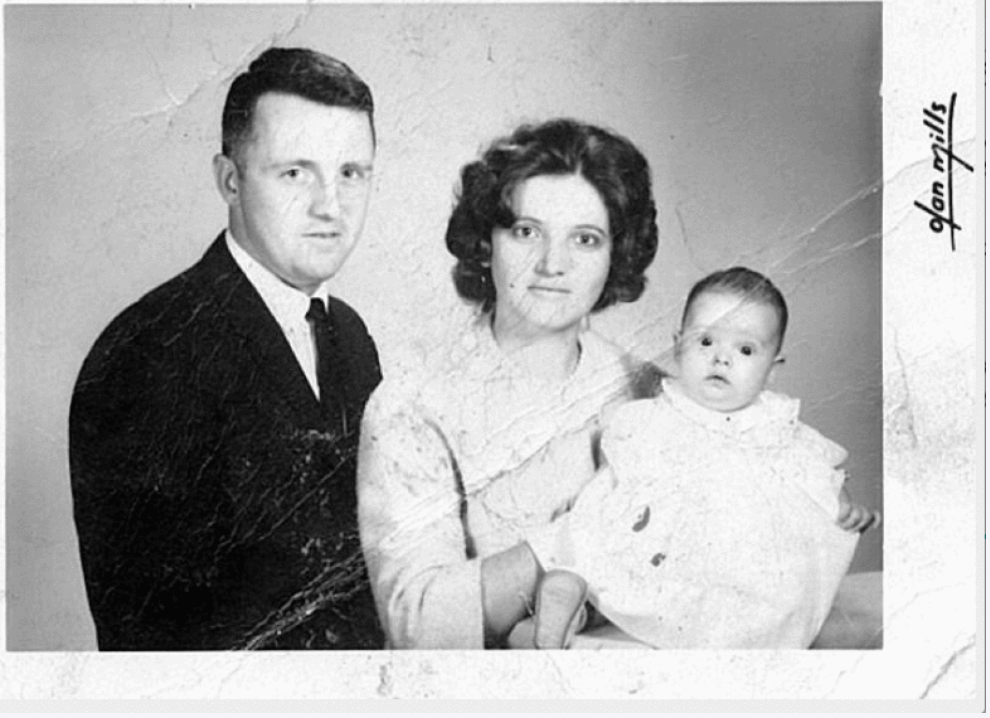

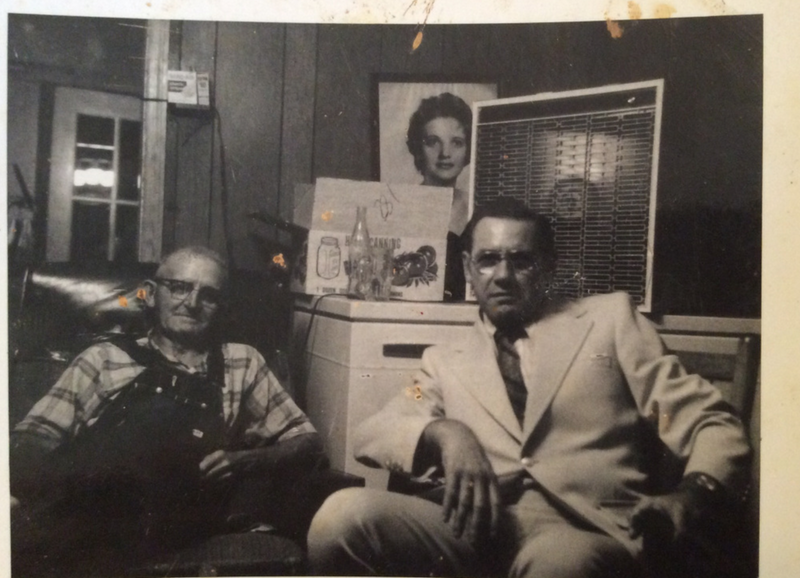

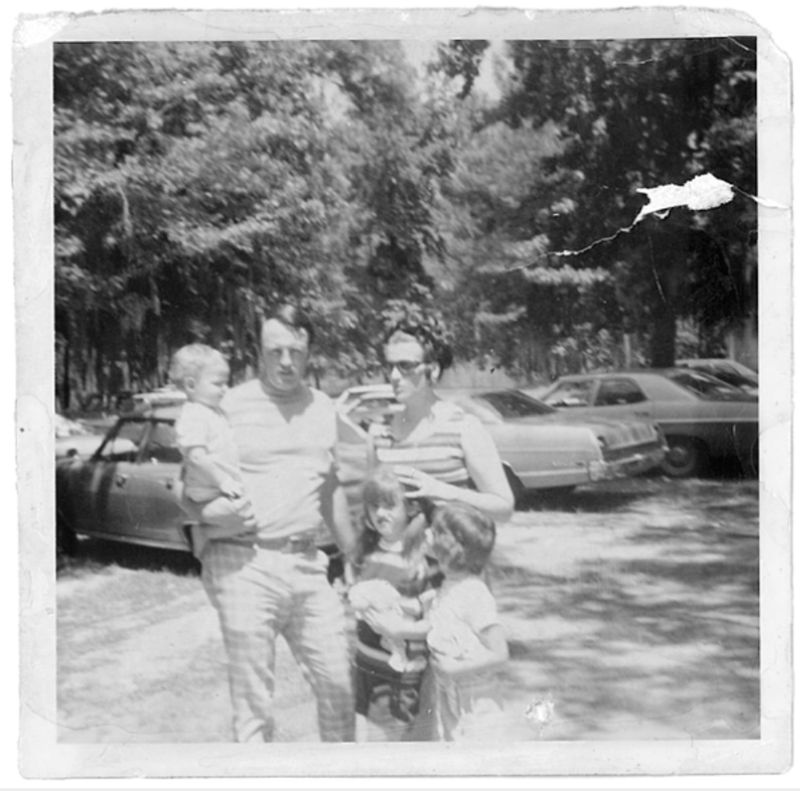

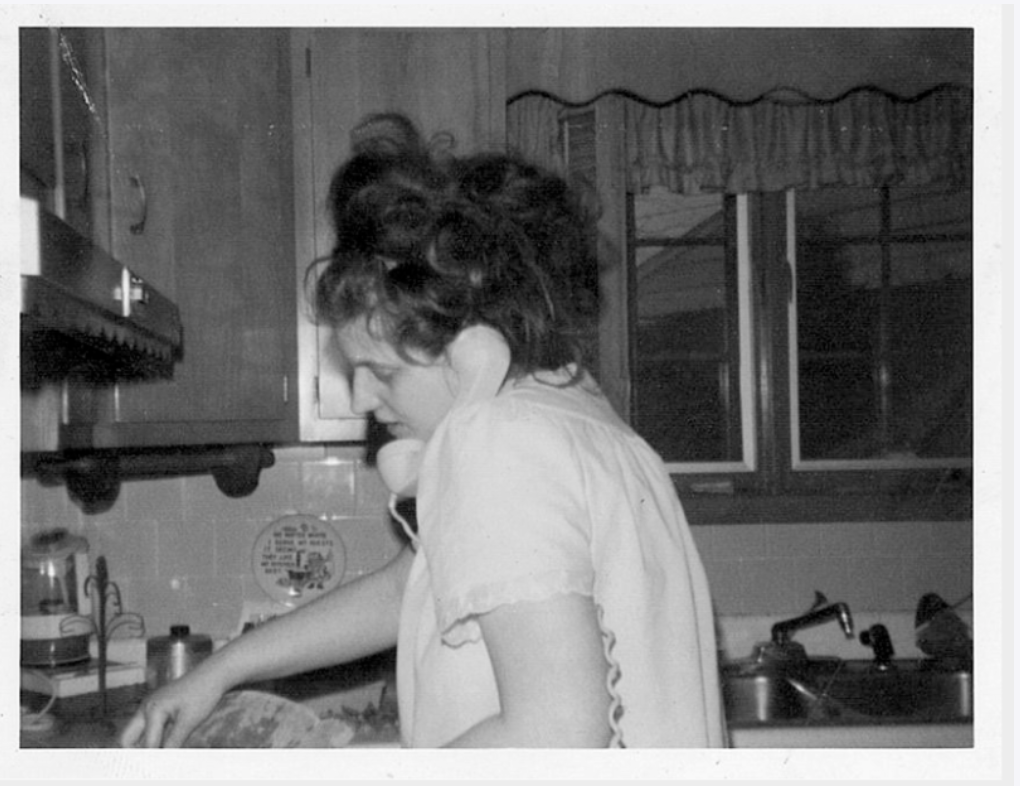

Two years ago I had an epiphany about my mother. Throughout our relationship she suffered serious mental illness. Her problems took many forms: narcissism, lack of inhibition, lack of impulse control, psychosis, depression. There was never one label that “fit” my mother. She left the many psychiatrists and psychiatric hospitals with a variety of diagnoses: depression, paranoid schizophrenia, manic-depression, schizophrenia. Her family’s explanation was “She’s just Bunny being Bunny.” The epiphany I had was: maybe the brain surgery mother had in 1970 was psychosurgery (similar to a lobotomy). It was like a voice coming forward from a vast history of silence. I had grown up knowing my mother underwent brain surgery in 1970 just a few weeks after my brother was born. Her version was that she’d suffered a stroke and almost died. My mother was the only one who ever spoke of it. That also seemed a little weird to me. I had an intuition that my mother’s version was fiction. Maybe my mother had a lobotomy. I told my sister and brother and last spring I started researching lobotomies in Massachusetts in 1970. I found some interesting information that strongly supported my hypothesis about my mother. The biggest clue was how my mother always told us that during the surgery they had drilled two holes in her skull to release the pressure. She had often pointed to the location of the holes and we had all felt the soft indentations on the back, top part of her skull. We felt the soft skin and could easily feel the permitter of two perfectly round holes. The location of the holes drilled into my mother’s skull were in the same proximity as x-rays I found of psychosurgery being conducted in Massachusetts in the 1970s. This resurgence of brain surgery in the 1970s for emotional and psychiatric problems is a little talked about, nefarious era in psychiatric practices. Like the predecessor frontal lobotomy, psychosurgy in the 1970s exploited the most vulnerable populations of individuals with and without mental illness: minorities, women, the institutionalized, children, and individuals with disabilities. These psychosurgeries differed from the older lobotomies in a number of ways. There was less impact on personality. Instead of targeting the frontal lobe of the brain, 1970s psychosurgeries targeted parts of the brain’s emotional center, the limbic system. As you can see in the x-ray above, small wires were inserted into holes in the skull and through “x-ray” mapping and stereotactic surgery (see images below), a wire was inserted and specific limbic structures were cauterized (i.e., burned with wires or sometimes hot wax). The following images were taken directly from “Violence and the Brain” by Vernon Mark and Frank Ervin (two major figures in the 1970s psychosurgery movement). As I continued to research psychosurgery, it became more plausible that my mother did–in fact– undergo one of the psychosurgery procedures in August of 1970. I found out that Massachusetts was the epicenter of psychosurgery at the time. In fact Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital received a large NIH grant to study “aggressive behavior,” brain disease, and research the effectiveness of psychosurgery as treatment. Two prominent Harvard doctors, Mark Vernon and William Sweet proposed screening African American males in response to the race riots taking place during the time. Their racism was met with a strong and swift response from activist both within the African American community and other human rights organizations. However, psychosurgery was on the rise in the early 1970s. One doctor –Peter Breggins, also from Harvard– began a crusade against psychosurgery. As a result the Harvard NIH grant was withdrawn and regulations were established to protect patients and insure informed consent. These changes were not in place until after 1975, five years after my mother underwent surgery. As far as my mother’s case, by late summer this past year I’d found a strong body of evidence to support that my mother had undergone one of these psychosurgeries. Not only was the hospital where my mother’s surgery performed less than an hour away from Boston, but my mother had been receiving psychiatric care by a psychiatrist who had studied in Boston and completed his residency at a state hospital where psychosurgeries were being conducted. I believe my mother had been under his care prior to the surgery and continued under his care immediately following the surgery and for many years there after. Immediately following the surgery my mother suffered from agoraphobia and severe anxiety and was put on anti-psychotic medication (prolyxin) and tranquilizers (valium). I have vivid memories of my mother after the surgery. While I was only five years old at the time, the change in my mother must have been startling and dramatic to me. Her head was shaved and she was unpredictable. Her eyes had a dark, evil look and she became manipulative and mean. My memories are hazy before that time but I remember the shock at terror over how my mother had changed. Concurrent with my research about psychosurgery in Massachusetts in the 1970s, I also conducted interviews with my sister, brother, and our kids in order to get a sense of everyone’s memories of my mother and thoughts on what may have happened to her. I also went through old photographs and letters (the few I had left–my mother and I had been estranged for over 20 years). I knew that at some point I would have to talk with family members who knew mom before and after the surgery. When my mother underwent brain surgery all of her relatives from Georgia (her sister, brothers, and mother) all traveled to Massachusetts to be with her. My mother’s brain surgery was a serious event. My mother always said she’d gone into a coma, was close to death, and then came back to life. So, these maternal relatives all have some information about the event. There are several surviving relatives who likely have information about my mother before and after 1970. The rest of the family, including both my parents, have passed away. Ironically, several years prior to her death my mother had begun researching her brain surgery. She had ordered her medical records and was trying to find someone who could decipher them and tell her what happened. Sadly, at that time no one really took it seriously. It seemed like another one of my mother’s crazy stunts or schemes. The records have since been lost and are no longer on record at the hospital. In my mind, my mother was a very different person after the surgery but she did have mental health problems before the surgery. I know she suffered from postpartum depression and psychosis. I figured she probably had an episode after my brother and the decision to do the surgery came after that. I’d also grown up knowing my mother had been in a car accident in 1957 and was unable to finish high school because she’d needed wrist surgery. I wondered if maybe she had a brain injury and that had something to do with her underlying mental illness. I decided to contact some of mom’s relatives. People I hadn’t spoken to in decades. I was afraid to contact these relatives because I had been estranged from them for over 30 years. It wasn’t so much that I feared this side of the family–they were all very kind to me growing up– I was afraid to open any door to my mother’s life. She had abused me and her family loved her, knew a different person. About a month ago I called a cousin of mine who grew up with my mother in Swainsboro, GA and lived near my mother for the last 20 years of her life (my mom died in 2008). After my parents divorced in the 1980s my mother moved from Massachusetts back to Georgia. At the time of the call, I hadn’t spoken or seen this cousin in over 25 years. The call and information my cousin shared opened a whole new understanding of my mother’s mental illness. Three things stood out from our call. The last likely –at least in part– explained my mother’s underlying mental health problems. Or more accurately her personality disorder. The first piece of information my cousin shared was that my mother had been in the army in her late teens. This was completely new information. I can’t picture my mother with her lack of impulse control doing very well in the strict rule-governed U.S. military. Why had no one mentioned this to us kids? The second insight came from my cousin’s response to a bit of information about my mother that I knew: my mother had lived in Texarkana sometime before she met my dad. She married my dad at 21 so if you count her time in the army and her time in Texarkana she would likely have been pretty young when she left home. I asked my cousin about my mother moving to Texarkana. “Well that isn’t so unusual, a lot of teenage girls did at the time.” Hmmm. Her apprehension made me wonder if I have a long-lost sibling somewhere. The third and final piece of news answered at least some of my questions about my mother’s mental state and it started a new line of inquiry. My cousin told me about something that happened to my mother when mom was a young teenager, probably around 1956 (my mom would have been 15). It went like this. I asked my cousin, “What was mom like before the surgery?” “Bunny was Bunny. You know she is just who she is. She would get an idea in her mind and she would argue the point and not let go.” “So there was no difference after the surgery?” “Not that I knew of. Of course I was graduating high school at the time. I was young and caught up in that.” “What was she like as a teenager?” “Well you know Bunny. She’d get something in her mind and wouldn’t let it go. I remember her telling daddy that when she turned 16 she was moving out. On her sixteenth birthday daddy knocked on her door and told her ‘well, you’re sixteen. I suggest you pack your bags.’ Your momma packed up a suitcase and walked over to her aunt’s house. She stayed there about three days and then came on back home. You know how she was. Stubborn. Won’t let anything go. She was just larger than life.” Then, my cousin then told me something I’d never heard before. “When your momma was a young teenager she was out sitting on the hood of a car with a bunch of kids, just hanging around the way teenagers do. She was sitting on the hood of the car and someone backed the car out. Bunny fell off of the hood of the car and hit her head. She was unconscious for 3 hours and when she woke, momma [my cousin’s mother, Betty] told me that m Bunny was just never the same after that.” I’d never heard this story before. So, my mother had at least two brain injuries. The fall off the hood of the car and the brain surgery in 1970. It seems likely that while I wanted to believe my mother’s mental illness was caused by her brain surgery, more likely I lost my mother long before I was born. Now I want to know who she was and what her personality change was like. I know very little about traumatic brain injury but I think it might explain some of her underlying issues with impulse control and lack of inhibition. Not very good qualities for a 1970s wife and mother suffering from postpartum depression. This November I am going to visit my remaining family –including my mother’s sister, Betty. I’m going to my mother’s home town of Swainsboro, Georgia and interview anyone who knew my mother in high school. I will go through old newspaper archives at the Swainsboro Blade looking for family information. I will visit places she lived. I will try to immerse myself in my mother’s life as it was in the 1950s before and after her head injury. I don’t know what –if anything– I’ll find out. It seems my journey is taking a slight turn, maybe the search is already over. My mother most likely had undergone psychosurgery in 1970 but that’s not the whole story of her mental illness. Now there is more to uncover. My brother is joining me and my nephew is going to film the interviews and investigation on an old video recorder. Here is a clip from an old Super8 of a family visit to Georgia a year before my mother’s surgery. Related Content: What Remains Inside, Memoir In 1981 I was fifteen years old. My mother was having a psychotic breakdown. Over the course of that year, her fixations on me intensified. At first she said I 'was' her. She tried to convince me I would be the next victim in a string of imagined crimes. Most days, she'd describe the murder scene; how I would be killed. I'd listen to her with rapt attention, fearing that what she was saying might be true. I'd watch her eyes examine me and I never really knew if she believed the things she told me or if she just enjoyed watching fear consume me. I'd leave my house at night, my emotions in shreds, the fear and paranoia having settled in every muscle in my body. My heart raced and my brain remained constantly vigilant. In the midst of my trauma, I found another place. Drugs. Alcohol. Boys. I'd guzzle cheap wine and wait impatiently for it to dull my senses and grant me power. Sometimes I'd take LSD or get so high that I didn't remember blocks of time. I'd sit with my best friends on the hood of our car smoking cigarettes, our feet in high-heeled Candie's sandals swinging to the beat of another car's radio blaring Led Zeppelin somewhere in the nearby darkness. When the crowd began to disperse, I'd find one of the handsome boys, make out and bask in the kind of attention I never tired of. I'd extend the nights for as long as I could, the fear of my mother a constant flicker just beneath my consciousness. My Journey to Audio Storytelling and the Potential to Shed Light on Experiences of Oppression7/7/2021 The Diarist (as most of my writing) uses expected tropes in the same way that virus technology programs a benign cell to carry a deadly disease. I intentionally embed these themes of oppression in familiar, palatable tropes: romance novels, stylized 1950s story worlds, and relationships that looks so much like intimacy that you “feel” love you should not feel. At least, that’s what I try to do.Years ago during an acting class rehearsal I stood on an empty stage and looked out at an empty black box theater space. The tech folks were adjusting lighting and no one was really concerned with actors mulling about waiting for rehearsal. I was experiencing a quiet and intense epiphany. Theater as political action. This -of course-is not a new concept but to me, a survivor of trauma including sexual assault by a stranger, I realized that if you can write well enough to “suture” your audience into the story, relate to the characters, and experience the events with empathy and compassion then maybe people will understand. Yes, this is hijacking our emotions, “catharsis.” Again, nothing new here, but new to me.

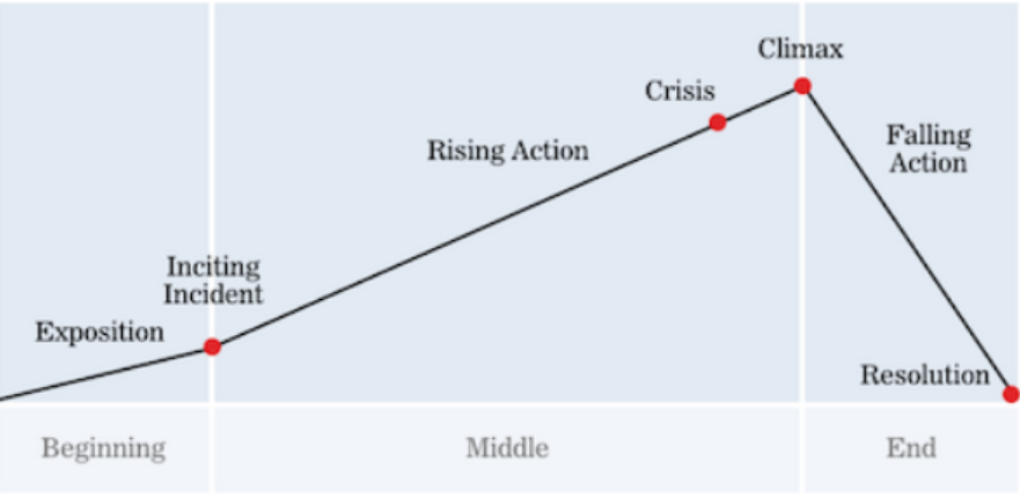

You see I have always-desperately- wanted people to understand the truth. I have always been spell-bound (in a bad way) by the cognitive dissonance associated with being a victim/survivor of child abuse and later violent sexual assault. One problem was -obviously- that some bad people did cruel things to me. Believe it or not, that wasn’t the most traumatic or damaging aspect of my traumatic experiences. The worst part was a silent world of witnesses. I have always been someone who either didn’t get social cues so well and missed the taboo topics in my dysfunctional family. I’ve also been someone thanks to ADHD that cannot suppress my thoughts and feelings. Finally, I’m -by nature- gullible and that made me prey to all sorts of gaslighting. These qualities or defenses also gave me a “Casandra Complex,” spilling oceans of truth to a world that reacted by blaming me and calling me crazy. So there I was, looking out into the empty theater and was struck with the powerful desire to become a playwright. This was no easy goal. At that time I’d only written short stories and those were still in the painful early beginning of the learning curve. I was not always a strong writer. In fact, due to dyslexia and ADHD (I’d find out at 50), reading did not come easy to me. For some reason -ironically- writing was always a psychological, spiritual, and emotional mandate. I started writing at 13, first diaries scribbled on loose leaf paper in red or blue pen, things like “why does mom have to get drunk all the time,” and “maybe I should become a slut.” I remember these two entries in particular, the first an obvious reaction to a painful home life. The latter, the desire to become promiscuous, likely some distortion of my emerging puberty and the effects of sexual abuse. I’d crawl under my 1970s, Sears, maple canopy bed and I’d write my secret desires and thoughts. With no boundaries and the risk of the worst kind of exposure, I’d fold the papers and tuck them deep inside the box spring through a small opening I’d made by ripping the fabric on the bottom. There they stayed. Years passed. I moved out. I didn’t retrieve the pages. I don’t know where they went. As the years passed I started writing fiction and my stories came as if channeled from some remote region of the collective unconscious. The point of view was always a woman, often in some dysfunctional entanglement with a man or with a family. Two Cent Return (the story of an orphan girl who runs away to find a ‘tramp’ living on the train tracks, she found an unlikely father and together they collect bottles and return them for the 2 cents. Unfortunately, a social worker finds out the abused child is living with a railroad tramp and removes her from the only family she’s ever known). Shamrock (the story of a girl who’s mother is mentally ill and the girl watches the mother out in a field of daisies and realizes she can never truly know or understand this person who was supposed to love and care for her but never could). Mr. Buckley Hasn’t Gone Mad (a middle aged man makes the two hour trip once a week to visit his mother who’d abused him all his life. He feels trapped but cannot get out of the relationship. When she pours him a glass of milk, he knows she may have drugged or poisoned it. He stares at the milk through the whole visit while his mother prods him to drink it. Finally, the milk is warm and Buckley drinks it and heads home). These are the earliest stories I remember writing. I have no idea what happened to these either. I am guessing I left them in the trunk of a 1970 Dodge Dart I abandoned when I bought a one way plane ticket and moved from Massachusetts to San Francisco at 23 in 1988. I eventually moved on to long-fiction then play writing. Both pursuits were long, painful, and humbling. I wrote and re-wrote and re-worked, trying to figure out how in the hell to do it. I shared my work with friends or other writers who looked at me quizzically; could they have been any more disorganized or lacking basic elements of effective story telling. I had characters. Often I had plots, but technical skills, I lacked. I wrote novels and plays on thousands of pages of paper. I read book after book on “how to” write. Then, one day I was driving along the coast of northern California and I was in that absent, good-dissociative state. I realized I was thinking of a plot of a play. This play would come to be “Love is Enough.” In this story, a 1960s housewife, living with an abusive husband, dreams of becoming a Harlequin Romance Novelist. When her best friend tells her of a contest, she gets to writing. In the process she inadvertently brings to life and falls in love with a character (Marcos Van Der Burn) from her book “Love Is Enough.” (Love is enough to make this love affair real). As the story progresses, her husband Mike grows more and more furious and controlling. He doesn’t like Gladys’ new self confidence, one which allows her to “find herself.” Gladys is faced with a choice, but it it between Marcos and Mike or is it between oppression and interdependence. Let’s fast forward ten years. In almost the same way that Love Is Enough came to me in a lightening bolt moment of inspiration, my series of novels that follows the trajectory after a 1940s widow’s trauma at the hands of an obsessive and violent lover. Constrained by a society where her rights are less than the man who raped and caused her so much harm, the protagonist Eve can never really disentangle herself from Jeff. Instead, she bonds with the abuser, and lives a life (spanning 1940s-1970s) around and along side a relationship that is both ecstatically passionate and crushingly violent. This series of five books have been read over 100,000 times on wattpad, a platform I’ve used for my unedited first draft stories. By the fourth book, readers forgot the physical and sexual violence perpetrated by Jeff. Instead, many readers started rooting for the “love affair” commenting that “they’ve been through so much together” and “they really do love each other.” As the writer, I had an epiphany, if I can get readers to see an abusive marriage as a love affair, then I’ve been successful. Why? Because I know from personal experience that many of us do confuse trauma bonding with love. I know from experience that nothing is one dimensional, and while it would be neat and easy to digest if people could be reduced to good or bad; but, we know that is not the case. We distance ourselves from the truth of trauma, racism, misogyny, homophobia, violence (these days from sedition and police brutality). We “Casandra-ize” the victims by ignoring the truth or reducing it to sterile political rhetoric. We must feel the truth, we cannot describe it. Now, my journey as a writer has taken me to adapting these stories to audio fiction. My first show, The Diarist, adds a twist to the Mad Men genre, placing an ambitious 1950s secretary in the orbit of a psychopathic executive. Andrea Davies enters the misogynistic 1950s workplace with the belief that she can pursue a career in advertising if she works her way up. Along the way she catches the eye of one of the partners at Roth, Hayes, and Johnson and not too long after he seduces her and as she becomes entangled with his life she meets and befriends his “lunatic” wife. Andrea cannot see that Richard will draw her into the same fate as his first wife. That through the vehicle of the fairy tale love trope, he will systematically take her power and offer only a gender role that is growing increasingly obsolete in the 1950s zeitgeist. Richard is afraid-as men were-that they were losing their dominance. Yet, the gaslighting reality becomes another malevolent force, one that is far more destructive than the abuser himself. The women at the firm turn on Andrea. Her mother turns on her. Richard begins to exploit Andrea’s growing desperation and convinces her of her inadequacies and even toys with the idea that she is insane (like his first wife who has by the end of the season taken her own life, making room for her replacement). The Diarist (as most of my writing) uses expected tropes in the same way virus technology programs a benign cell to carry a deadly disease. I intentionally embed these themes of oppression in familiar, palatable tropes: romance novels, stylized 1950s story worlds, and intimacy that looks so much like intimacy that you “feel” love you should not feel. At least, that’s what I try to do. As I explore audio drama as a medium for story telling, I am delighted by the opportunities to harness cultural anchors to reinforce the experience of the female characters. Tropes were more salient and less apologetic during the early 20th century in America. Rules were different and consequences far more grotesque, unjust, and existential. In my new audio drama “Exuberance Is Beauty” I’ve attempted to apply long-form storytelling (novel) to the audio drama format. I see this experiment as a literary podcast so listeners are immersed into the world of the story through dialogue and sound-scape, but the narrative stretches across a season as you would experience in a novel. The narrative arch starts out a little slow, allowing for exposition and getting comfortable in the world of the characters and story. Yet, there is escalating tension and finally a climax that has been built in much the same way as a traditional novel. Admittedly, I don’t know if this experiment in literary storytelling will work for the fiction podcasting platform. It’s not an audiobook. It’s not a serialized story. It’s a scripted long narrative. Listeners will need patience (and interest) to get deep into the world of the story as foreshadowing, exposition, character, setting, do their alchemical work to “suture” the listener in. This is akin to a television mini-series drama. I am happily grappling with the challenge. I am excited by the potential to elegantly weave social, feminist themes into a compelling listening experience. Exuberance Is Beauty Literary Fiction Podcast The Diarist Fiction Podcast youtu.be/E0sha1XfHxw

Fleetwood Mac "Hold Me" released 1982 I do t know if it’s optimism or cynicism but I hear these old songs and a wave of relief washes over me, rushing in with the kind of centering that happens after a trauma averted. But it’s not a trauma, it’s the sum of my choices. This song in particular (and be it said that my lens has always been sharply focused around the fate of romantic love that deceptive sensory mystery) and this particular song is a reference back to this kid, the brother a terrible horrible teenage misogynist (that I happened to think I was in love with - no that minimizes it too much reduces it). I’m my 16 year old mind / heart/ body he was an apostle of Aphrodite - he was my one true love and just because it looked like the back seat of a car , super drunk, after no one else was left - to me. This guys brother was going to be my husband. I Hear a Symphony pealed as I walked down the aisle. This song -Hold Me- doesn’t remind me of the boy I was infatuated with. It reminds me of his brother. It reminds me of feeling bad for the younger- looking version of my soul mate. The pangs of regret are because he actually liked me. He'd spent so much time convincing me that his older sibling was cruel to me. I felt bad because part of our bond was hearing the mention of his brothers name; it was talking about him without the judgement of my friends who were sick of my obsession. So I dated his brother — maybe only for this reason. So here now, 40 years later. (Yes I tell myself that is possible that it's been 40 years and I know it is because this memory is contextualized in another lifetime -the 80s- and even for me it takes Google searches for visual reminders of interiors of 1970s Pontiac’s or Chevies, cars with no such thing as Bluetooth, never mind a DVD player. Cars with no automatic or intermittent wipers, cars with the smell of leaded gas. It was a time when global warming doesn’t exist. No cell phones - few computers. More than that. It’s my youth - that miracle of my undeveloped frontal lobe and floods of dopamine over the reptilian parts of my brain. It is hormones and a fertility-imperative bathed in the sounds of Donna Summer in dark nightclubs where no one questioned IDs because drivers licenses were typed on card stock with a photograph. Driver's licenses with lamination that was easy for a 16 year old identity thief to use their coke-razor to carefully remove one 25 year old girl's photograph can replace it with one of my 16 year old face. Obvious but sufficient. I do think about it when the song plays. Fleetwood Mac's Hold Me. Mark. Mike's brother. Nice guy. Sweet and comforting. Knowing (maybe) that it was my final attempt to make Mike jealous. To hasten that proposal I knew would come. To speed up the planning, the Supremes timing giving way to Here Comes the Bride on the organ in the Gothic Catholic Church where I'd been baptized and confirmed. My inevitable marriage to Mike, the final sacrament before the Last Rite. A sacrosanct pact forever that would keep Mike from choosing another girl to sleep with after a house party. Oh, how I'd thought it would have been romantic; his indifference and rejection a thin shield protecting his true feeling for me. Now I listen to Hold Me and I whisper to myself: "Thank you God for not granting my wishes for a lifetime with a man like Mike or even his brother Mark." I cyber stalked them both not too long ago. I did it because people do. It's called cyberstalking but really I just visited their Facebook pages. I just peeked into their lives and not for very long at all. They’re old. I’m old, so that’s ok. They’ve gained a lot of weight. I have too. They’re still living in that Massachusetts town. I’m not. "Fuck You liberals" they post in their status. Their faces are ruddy from Alcohol. I don’t see pictures of women or children on their pages, though likely they have them or at one time did. I see them with the same group of football players they have been buddies with since high school. Back then, their status as sports stars, was was a transitory illusion but I believed it. I thought sex was love and I thought my own adoration for a boy was romance - to me it was. Girls back then did end up pregnant or somehow otherwise married to these fantasy men. That was the fate I'd prayed for God to grant me. I wanted to end up pregnant or somehow otherwise married to Mike. Time passed. I remember college and revisiting the old life I'd once lived. Being at a party and somehow afterwards ending up on a basement couch and on the floor in a sleeping bag, Mike. I should have recognized his form under the cover. We were together again, just him and me, alone all night. This was my 15 year old dream come true. And maybe this very circumstance had been one of the plots or one of my obsessive day dream narratives. I go to college somehow become beautiful and sophisticated. I’m wearing high boots that I could never have afforded. Maybe I was at Harvard and it was fall and I’m in a bulky oversized sweater and jeans. I’m different somehow with my pearl earrings. I’m engaged but I don't love my fiancé. I still love Mike. So I return home over holiday break, back to my gritty Massachusetts fishing town. Mike's a contractor maybe a house painter. I return home and walk past a house. I look up and just like in a Rom Com, he’s there, up on scaffolding - he reflexively starts to cat call. but then he stops. Our eyes meet. He’s Rob Lowe. I’m Demi Moore. Time really passes. I go to the local state college not Harvard. I study psychology and several of my professors suggest to me that I’d been abused as a kid. One gives me a book of short stories meant to be read to your wounded, inner child. The story my professor tells me thatI should read is about a little child who busies herself so much with daydreaming that she can’t live in the real world. It speaks to me, but I don’t know what it means. We do find ourselves after high school and we are in this girl Sandy's basement. We're drunk: Just Mike and Me. I wish I could say it was payback or as they say now "taking my power back." But it wasn't either of those things. It was just nothing. Mike's disembodied voice broke the quiet of the dark basement, “Remember when we used to go out?" he asked. His voice revealed a vulnerable intimacy in that dark space. “No” I said.

This is a draft chapter of a a guide book, a reflective journal, a record of inspirations. It is my hope that those interested in adapting their fiction (or nonfiction) to a podcast, will find helpful information to start their journey. No one can deny creative writing is an intensely personal process. For as many writing “how to’s” there are methods -often idiosyncratic- that writers employ to spark their imagination and engage with the written word. I am no different. To say I love writing is not entirely accurate. Rather, writing is essential to who I am and how I see the world. I had an interesting conversation with my husband the other day. He is a musician and a visual artist. We talked about how we navigate the world, move through everyday life. He said he notices lines and shapes of things in the world. When his mind wanders he is engaging with the visual qualities of life. That is not my way of thinking at all and I suspect it is not how most writers experience life. Rather, my mind is constantly constructing narratives, even without my knowledge. I’ll find myself “zoning out” and realize I’ve just made up a story about the lady in line at the grocery store. There is a constant stream of narrative.

I have been seeing the world this way for as long as I can remember. Getting through aversive tasks like cleaning my house as a child, I would contrive Dickensonian scenarios where I was a poor girl in rags going through the drudgery of everyday life, with a limited awareness that there was world of childhood delights for some other fortunate girl. Dramatic I know, but I ran these stories in my mind and they preoccupied, distracted me. When I was 14 I began writing, out of curiosity about my developing / coming of age self. I wrote about things adults did with the hope that this current of narrative would reveal life’s truths. Recently, an old friend who I am connected with on Facebook wrote and told me she had a stack of stories I had given to her thirty years ago when I was in my early twenties. She agreed to send them to me and I — honestly — was a bit dreading the idea that these stories would be so full of narcissism and writing blunders…some were, of course. However, I found one story I didn’t remember writing. The language was simple and concise. It was an incredibly sad story with just a hint of hope at the end. It was short: only five or six pages but reading my words from so long ago left an indelible impression on me. I had something to say and it was deeply sad at the time. I had something to say because I wanted other people to read it and understand. Writing allows one to engage with the complexities of life’s experiences. It is emotional, intellectual, and political. I love writing for these reasons. When I was in my mid twenties I enrolled in a Stanislavsky acting program. I was not such a great actor, but through character and script analysis, a new potential for writing revealed itself to me. It was different than the stream of consciousness, loose narrative structures I had employed in my previous writing. I can remember standing on the stage — a tiny black box theater at the school — with the lights beaming down and a new potential for writing was revealed to me. I began studying the art of dramatic writing. It was entirely different and I knew it wouldn’t be easy (since I wasn’t even quite accomplished at constructing a narrative structure), The well known, narrative arc, was still elusive to me:

Ah, the elusive story structure. Seems simple enough right? Hmm…well more on that later.

I began reading and studying script writing. I wrote and wrote and wrote. I worked at an office job where there was literally one or two customers in an 8 hour shift. We used one of those old dot matrix printers — most probably don’t remember those I’m sure — and and on the backside (no two sided printing back then!) I wrote my first play — or tried to at least. I forget what it was entitled but I sort of remember the story. There was a family — dysfunctional — and they all return for their father’s funeral. He had written his biography that included the family secrets on note cards..then he spread them all over the old dilapidated mansion. The siblings all arrived, full of the normal dysfunctional family sibling conflict. The play was full of avant garde devices (read: completely confusing). I layered monologues one over another. I had ghosts and gibberish. I basically threw all of the absurdist tactics I could into my story. I was a HUGE fan of Edward Albee and his uncanny dialogue — capturing subtext in seemingly inane conversation. I loved waiting for Godot. Ionesco. I also LOVED Tennessee Williams (so I threw a few scrims in there) and Eugene O’Neil (made it long, very long). For all my investment and good efforts…it was not a play. Rather, it was hundreds of pages of words written on the back of long perforated sheets of dot-matrix printer paper. As we all know critics can be cruel and in my case this was exceptionally true. I had a good friend (well regarded writer now) and I shared my play with him…someone told me — I don’t’ remember who — that he and his roommates had posted one of my more melodramatic and terrible monologues on their refrigerator for a laugh. I had a thick skin because I genuinely thought it was Pulitzer worthy and I kept writing…and some of my early one acts started to resemble plays. Since that time I have had minor recognition for a couple of my plays and I “get” some of the basic technical aspects of dramatic writing (more on this later too). So that is the background on this adventure I am now undertaking: adapting a novel for radio. This too has been an enormous learning curve. Writing for radio involves more dimensions to constructing a story. There is still the story structure, technical elements of script writing, and an engaging story. Add to that, adapting the arc to stretch across 15 episodes (8 hours of audio). Add to that the potential and downfall of audio / soundscape. It’s been a journey and it’s not over yet! These chapters will share what I’ve learned as I adapted my novel The Diarist to a serialized fiction podcast — The Diarist Podcast — launching March 2018. First I’ll present a background and tell you a little bit about the story The Diarist, how it came to be, and why I thought it would make a good podcast. These were the early days…recording the story — as it was in narrative form — on a cheap microphone on my broken laptop (boy did we come a long way!) These early attempts at creating audio drama helped me sort out whether I wanted an audio book or a scripted podcast. After this introductory / background chapter I’ll share some of what I know about fiction writing and script writing; the similarities and difference. Think of this section as back to the basics of writing. Plot, structure, elements of conflict and action (and character, and setting, and voice…). Later on in the book l will compare examples from the novel and analyze how I transformed prose to script (you’ll get to hear some sound clips from the podcast too!). I will next share with you inspirations for the story: a lot about research: historic photographs, newspapers, stories, friends. Now for the steep learning curve. I will spend some time sharing what I’ve learned about podcasting — the technical, financial, and practical aspects. Part 2 of this book will contain a lot of resources and links, Q&A from podcasters in the field, and a breakdown of the steps I took to go from a draft novel to a clean, well-produced, 15-episode audio drama. A How-To-Podcast handbook would not be complete without a step-by-step outline of the process…from script, finding actors, to hosting, to fund raising, to launching, to maintaining social media campaigns. I will end the book with a series of interviews with my cast, director, and sound engineer…and a Diarist Podcast Scrapbook, complete with rehearsal pics, excerpts from the script, audio clips, and more!!! At the end of each chapter you’ll find “The Pulse of Podcasting,” these are actual conversations drawn from online podcasting groups…it puts all this into context (or at least it’s a reminder that you’re not alone!) The good news is there are a lot of really cool people out there podcasting amazing stories. It’s also a relatively niche to break into. And it’s fun!!!! I was in another place. Everyone else was in the ‘real world’, a pretty summer day, cool refreshing beach water, already a bowl of watermelon on the table. But, I was not there. I was in the morning with the atmosphere of dysfunction that I had grown up with. It was a seriousness that stopped the activities of real life. It was the same as a real emergency but it was imagined. All through my childhood my siblings and I trekked back and forth between real emergency and imagined crisis. All the while watching the landscape of normal lives right there, but passing us by. Maybe that is what it is like to have a mentally ill mother: trips to the emergency room, suicide attempts, police visits, imagined dangers, affairs, break-ups, pretend run-aways, sharp objects on flesh. And, what does this all mean? Does my PTSD make me, too, a ‘mentally ill’ mother. But, I do not — or I think I do not — do harmful things. Was my choice to drive to North Carolina that day a choice that came from my mental illness or was it just an impossible situation; was it the internalized obligation of seeing my dying mother? A prisoner. That was how I felt that morning with the southern heat starting up, the ocean-with that horrible undertow-crashing rhythmically outside of the glass doors. The kids laughing and pulling on bathing suits. I remember I was so angry. I was furious with my sister and brother — for not wanting to talk about it. My brother’s perspective was that he had been dealing with it in real life and wanted a break. He had every right. He was the one who took the daily calls from her, kept secret his knowledge of my and my sister’s private lives, visited the hospital, listened to her fabrications and pleas for attention. He tolerated her verbal abuse and narcissism.

Memoir Video Excerpt & Personal Essay by: Donna Barrow-Green BOOK SUMMARY: In 1981 I was fifteen years old. My mother was having a psychotic breakdown. Over the course of that year, her fixations on me intensified. At first she said I 'was' her.' She tried to convince me I would be the next victim in a string of imagined crimes. Most days, she'd describe the murder scene; how I would be killed. I'd listen to her with rapt attention, fearing that what she was saying might be true. I'd watch her eyes examine me and I never really knew if she believed the things she told me or if she just enjoyed watching fear consume me. I'd leave my house at night, my emotions frayed and bare, the fear and paranoia having settled in every muscle in my body. My heart raced and my brain remained constantly vigilant. In the midst of my trauma, I found another place. Drugs. Alcohol. Boys. I'd guzzle cheap wine and wait impatiently for it to dull my senses and grant me power. Sometimes I'd get so high that I didn't remember blocks of time. I'd sit with my best friends on the hood of our car smoking cigarettes, our feet in high-heeled Candies sandals swinging to the beat of another car's radio blaring Led Zeppelin somewhere in the nearby darkness. When the crowd began to disperse, I'd find one of the handsome boys, make out and bask in the kind of attention I never tired of. I'd extend the nights for as long as I could, the fear of my mother a constant flicker just beneath my consciousness. AUTHOR VIDEO EXCERPT PERSONAL ESSAY: I had an acting teacher once who told the class “When Eugene O’Neil wrote Long Days Journey Into Night, he cried tears of blood.” So, I thought that writing the play was so cathartic for O’Neil that he released all of his heartache, loss, and pain; that he was transformed through the process. I don’t know whether he actually cried tears of blood or if that is even humanly possible but in years of searching for a sense of peace and resolution about my own difficult childhood, I hoped that I could heal through writing. I had hoped my pain too would spill on to the page and it would be left there, transformed into something universal, existential. In 2008 I completed a memoir about growing up with my mother who suffered severe mental illness. Her illness caused her to be abusive, narcissistic, and uninhibited. When I first wrote my memoir What Remains Inside, I wouldn’t say it was cathartic; it was more like channeling. It was almost direct re-experiencing of all that trauma. The process I went through was eventually transformative and healing but not in the way I suspected it would be. It was not crying tears of blood. At first, the mere act of writing about experiencing trauma as a child simply disrupted my internalized beliefs about myself. It unlocked several doors but still some remained closed. At first, upon reading and re-reading my memoir I began to parcel out old patterns of thinking. Ideas about myself that had been fossilized and continued to influence my actions and beliefs. Until I re-read my words from the vantage of a 40 year old mother, I had continued to believed that I was solely responsible for the things I did at 15 years old, as if there I been born to be the rebel that tore through my adolescence. I liked to see myself this way. I was powerful, maybe even super powerful. I believed I was able to smash through the invisible walls that would have otherwise kept me imprisoned — and I succeeded but it had been so risky — I never acknowledged that truth. I had no idea until I became a mother myself. I wouldn’t dare to imagine my daughter doing the things I did when I was a young teenager. Back in 2008 when I completed my memoir I was struck with a strong cognitive dissonance. Unbelievably, I had never thought of myself as having been a troubled teen. I never recognized how unusual it was that I drank and did drugs by the time I was 13 or that I'd started shoplifting at age 12. It didn't occur to me that most 15 year olds are not out driving around past 3:00 a.m.. Even in my early twenties when I worked with kids who had been abused, I never recognized myself in their “delinquent,” acting out behaviors — predictable reactions to trauma. So, initially it was not cathartic at all to write about my experiences with childhood trauma. I also hadn’t really understood how severe the trauma I experienced was. I had always redefined reality. As a result I gave a copy of my memoir to everyone I knew. Some devoured it page by page. It kept them up at night unable to put the book down, trying to reconcile my words with the person they knew — this typical mom that volunteered at with the other kindergarten moms. I had laid bare something I hadn’t been able to see about myself. Maybe this extreme act of disclosure was part of the process of acknowledging my own experiences and how much of my concept of self was tangled up deceptions I had constructed in order to survive. Initially, I had given the book to the wrong people. That was clear to me, after the fact. Still this painful exposure forced something to the surface that I had to — at some point in my life — deal with. I had been buried for so long underneath the possibility of being discovered, of having my painful story exposed. Some people spend their lives hiding from their painful experiences. I had been someone who announced it loudly but afterwards ran and hid. That is a horrible place to be. Today, almost nine years later my memoir is a document of my tragic childhood experiences, a case study of a teenager’s life decades ago. Recently, I’ve begun to look at the reasons for my mother’s mental illness and I’ve discovered some things I didn’t know. So I’m embarking on another layer of personal discovery and acceptance. I am now beginning to understand the larger context, beyond my own personal suffering. I don’t know if catharsis is possible or if Eugene O’Neil really had cried tears of blood. I think I understand that the journey is long, maybe endless. However, I see the other way around, from night to day.

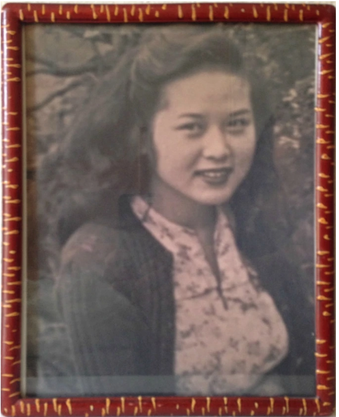

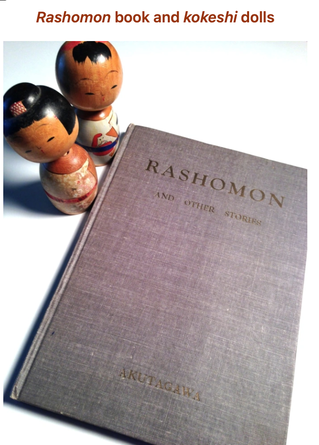

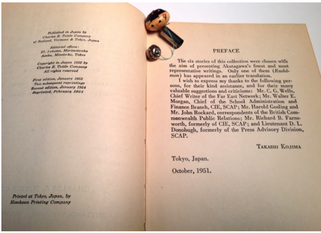

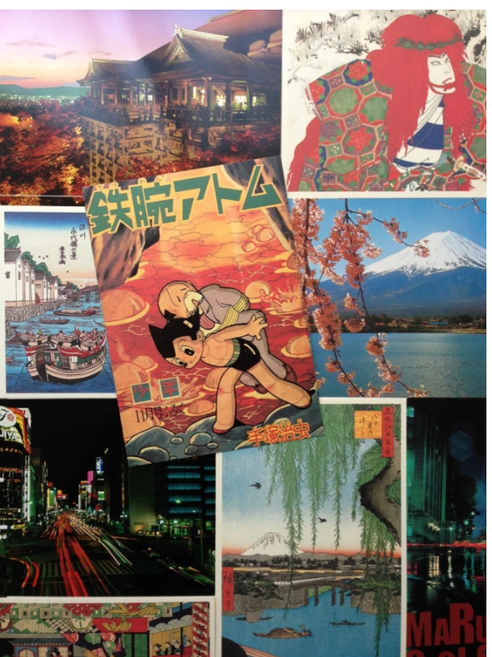

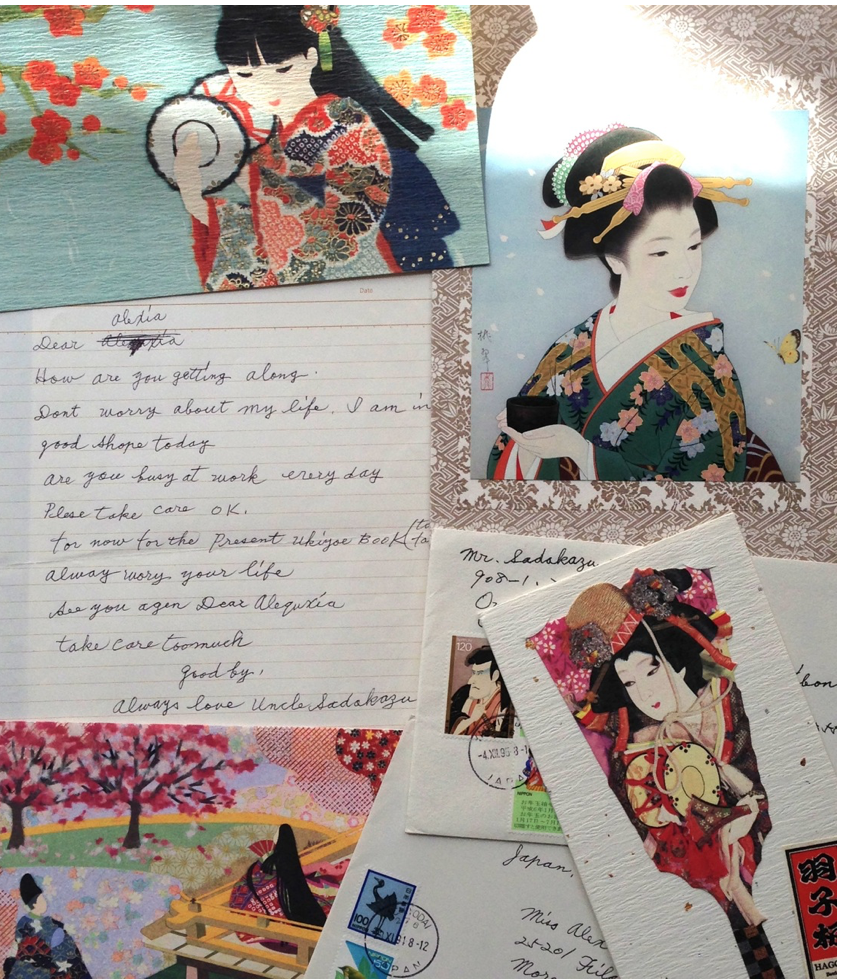

What Remains Inside on WATTPAD Author’s Note: Of course after writing this essay I googled “Eugene O’Neil tears of blood” and found this. Again, another dimension of understanding. On this day in 1941, on his twelfth wedding anniversary, Eugene O’Neill presented the just-finished manuscript of Long Day’s Journey Into Night to his wife, Carlotta. Accompanying the manuscript was O’Neill’s letter of dedication: Dearest: I give you the original script of this play of old sorrow, written in tears and blood. A sadly inappropriate gift, it would seem, for a day celebrating happiness. But you will understand. I mean it as a tribute to your love and tenderness which gave me the faith in love that enabled me to face my dead at last and write this play — write it with deep pity and understanding and forgiveness for all the four haunted Tyrones. These twelve years, Beloved One, have been a Journey into Light — into love…. (quoted directly from original post:http://www.todayinliterature.com/stories.asp?Event_Date=7/22/1941)  While browsing wattpad, I was fortunate to discover Alexia Montibon-Larsson's book Forged In Fire: Stories of Wartime Japan. It is an elegant and lovingly rendered memoir / oral history. Montibon-Larsson skillfully captures her mother's childhood experiences in occupied Japan following world war II . She reconstructs her mother's memories in a historically accurate timeline. Montibon-Larsson's meticulous attention to historical accuracy creates a dramatic tension throughout the story. We know the implications of escaping the desperate conditions in the city to go live with relatives an hour away from Hiroshima. Through her mother's words,Montibon-Larsson presents a culturally authentic account of family life in occupied Japan. The prose is so lovely and well crafted, but it was also the intimacy between Montibon-Larsson and her mother (Rita Tomoko Montibon) that captivated me. Admittedly, at the end of the book I wanted more. It wasn't that the story was incomplete, it was just so beautiful and welcoming I wanted to experience it a little longer. My interviews with Alexia Montibon-Larsson are presented in three parts (1) written responses to questions about her book and her writing process. (2) a commentary about several photographs of people or objects that have personal meaning and inspire her writing (3) an audio excerpt of her book Forged in Fire: Stories of Wartime Japan. Author Q & AAfter reading Alexia's book, Forged in Fire: Stories of Wartime Japan, I wanted to find out more about her and the process of writing her book with her mother. We exchanged emails and started the interview process. Early on I asked her to answer a few questions about the stories and her process. The book was so well structured and developed. Her mother's life stories followed a historical timeline. As I worked with Alexia more, I found out that there were many stages of interviewing, research, and writing. I loved the story but was also fascinated with the process of editing and synthesizing her mother's recollections then presenting them in a historically accurate narrative. QUESTION: Can you talk a little about the book? Forged in Fire is the story of my mother's childhood experiences before, during and after World War II in Tokyo and Kyushu, Japan. She was ten years old when the war started and fourteen years old when it came to an end. It recounts the hardships that she and her family endured and gives the reader a glimpse into what what life was like in Japan during those times. QUESTION: You must have heard many of your mom’s stories while you were growing up, what made you decide—at that point in time—to write a book about it? My Mom, along with my brother and his wife, had moved to New Mexico several years ago. My husband and I would travel to New Mexico once or twice a year to visit during summer and/or winter. Although my Mom was still fairly healthy, it was apparent to me with each visit that she was becoming more frail. Part of me knew that it was inevitable that we were going to lose her at some point and the knowledge of that impending loss pushed me to start the project. I knew it would be a daunting task which is probably why none of us (myself or my siblings) had yet gotten around to attempting the project. Mom and I worked on it together consistently over a period of approximately six months, up until a few weeks before she passed away. Of all of the children why do you think you were the one to do this project with your mom? That's a good question because I'm not entirely sure of the answer. Although we all have busy lives, I may have been the first to initiate the project because I knew somehow that there wasn't much time left and was driven to do one last thing for her: make her dream come true. How did your mom react when you asked her about doing the project? She was so excited about it. I'm sure she was thinking to herself: Finally! Where did you conduct the interviews? Over the phone or doing your visits? Initially, I conducted recordings at her home during visits. We would sit at her kitchen table and I would try to keep the conversation focused. We did about 2-3 of these sessions and after that everything else was done mainly over the phone. QUESTION: Can you talk a little bit about your process. How one would go about creating an oral history of a family member. My advice for creating an oral history of a family member is to collect as many stories as possible using whatever means are available or accessible: recordings; phone calls; photographs; documents; interviews with other family members, etc. Gathering as much information as possible in a short amount of time was the immediate goal. I had borrowed my husband's digital recorder to tape a handful of conversations between myself and Mom during previous visits. After uploading the files into GarageBand (an Apple music editing application), I transcribed the recordings. It's a time-consuming process that involves playing, stopping and replaying small snippets of audio at a time and writing everything down. To speed things up, I also wrote down the stories I already knew by heart in as much detail as I could remember. I would then call Mom with specific questions and we would have long conversations during which I would have my notes out so I could fill-in any gaps. These phone conversations inadvertently brought out more stories, some of which were new to me. As the writing progressed, I found myself frequently Google-searching details for clarification. For example, Mom had told me that she was pretty sure the name of the prison where the war criminals had been housed was called Sudamo prison. After fact-checking the name, I found that she had been close: it was actually called Sugamo, not Sudamo. That Mom had remembered as much about the name of a prison was amazing to me but normal for her. Her memory had always been sharp. If I had overlooked even the smallest detail of one of Mom's stories -- the color of some fabric trim or an ingredient in a dish -- she was quick to point it out to me. I ended up with many pieces and fragments of her stories but needed to place them together in a way that would flow naturally. It then occurred to me create a timeline as a reference. I printed out the long, rambling documentation I had accumulated on my computer and cut it apart into paragraphs, spreading them across the living room carpet. Using the timeline, the pieces were moved into chronological order. Distinct sections were revealed: pre-war childhood; school memories; wartime; and the Occupation of Japan. Once a rough order had been determined, I taped all of the fragments onto pieces of paper and used them as a guide for editing. There was a lot of cutting and pasting that had to be done but it took shape quickly after that and the timeline itself became a part of the book. Did you prepare questions in advance. Your book is so rich with specific detail, what kinds of questions or prompts did you use with your mom to get her to open up and share so much? Initially, I hadn't prepared any questions ahead of time. My mind was overwhelmed with all of the many stories she had shared with us throughout her lifetime and it was difficult to know where to begin. It started out along the lines of, Hey, Mom, remember how you used to tell us about how you would wander around the neighborhood and watch all of the shop keepers? She would say, "Oh, yeah," and start recounting everything in great detail. I knew most of her stories well enough that I could start writing them down on my own. It was during the process of trying to connect the dots between stories that questions would start to form. For example, I was confused about her time in Kysuhu. When did that take place? For how long? Did the process change as it went on? The process changed slightly when Mom started calling with more details. As memories were triggered, she would leave messages: "Alexia, I remembered something else today. Call me back." QUESTION: Were there unique challenges to conducting an oral history with a loved one? One of the unique challenges of conducting an oral history with a loved one is having to broach subjects or events which may be painful to that person. In this case, it involved discussing the death of Mom's aunt. Growing up, I had heard all of the many wonderful stories of Auntie's energy, modernity and creativity but could not recall a single story about how she had died. In order to complete the story, I was going to have to ask her about Auntie's death. Obtaining this information from Mom brought out a whole new set of stories that included details how dead bodies were handled in Kyushu at the time. Talking about Auntie's death unexpectedly triggered another wave of stories that revealed an abusive side of Auntie's personality. This was a shock to me as well as Mom. It actually upset her quite a bit and she experienced feelings of guilt for not having been able to help her brother, Tadashi, who had suffered the most. To accomodate this new information, the book had to be re-edited to include a separate chapter, "Fairy Tale Witch." Soon after, Mom called to request that Auntie be removed from the Dedication portion of the book and asked me to delete the sections that detailed Auntie's abuse toward Tadashi. A week or so later, Mom changed her mind and said she was okay with keeping the details regrading the abuse in the story because it was the truth of what she and her brothers had gone though together. Did your mother express to you what it meant to be able to talk about these memories? Both with auntie and also the horrors of war? Had she shared these memories with anyone before you? Mom did tell me that she was glad I was recording her stories for her but didn't express what it meant to talk about them. It occurred to me much later as an adult that the act of sharing her experiences had already been a form of therapy for her. As children, we knew the the horrors of her war experiences, mainly the ones about how she and her family starved; how her school was burned to the ground; how the sky turned blood red; how Sadakazu had to give up their heirlooms to survive. We also knew that Auntie was sometimes harsh. I was familiar with the story of Auntie hitting my Mom on the head with a pencil case but the more disturbing memories, like seeing a dead man lying next to a railroad track or witnessing Auntie kicking Tadashi were not shared until the project had been going on for some time. Mom had on rare occasion shared some of her stories with people outside of the family and was almost always encouraged to write a book. It was a lifelong desire for her to do so but she didn't have the time or energy to actually go through with it. How did your siblings feel about these new insights into what your mother went through during the war? I think they were as surprised as I was about it, particularly the new stories about Auntie. QUESTION: Were there things you learned about your mother that you wouldn’t have expected? Yes, I learned much more about what drove Mom's impulses, motivations and hopes for her family. Her wartime stories had always been a huge part of my own childhood experience but I gained additional insight into who she was as a person by writing them down. Everything she had seen, felt, lost and endured during the war years shaped who she became as an adult and as a mother. It explained a lot to me about her values; her devotion to American citizenship; and the fierceness of her love for us. QUESTION: Did your mother have any feelings about the US and the way Japanese Americans were treated here during WW2? I know she felt the forced internment of Japanese Americans was a sad and unjust act but she never spoke of U. S. wartime actions with anger or resentment. It was simply not part of her mindset. One of the stories she enjoyed recounting was how when she was interviewed for U. S. citizenship, she had been asked if she would be willing to die for her country and she had not hesitated to answer "Yes." She felt becoming an American citizen was a great honor and privilege and she never took it for granted. QUESTION: How were the wartime stories a huge part of your childhood experiences? How she express these memories / experiences? Mom's stories filled my imagination and I never grew tired of hearing them. Listening to her descriptions of people, places, food, dress styles, traditions and events, including wartime events, was a pleasure not just for me but my siblings as well. The feelings Mom had experienced came across in her storytelling: her curiosity; delight; excitement; frustration; sadness; despair. Her storytelling fueled my love for reading and the visual arts. QUESTION: Did your family keep albums or photographs of the places, people, in the book? Mom was the family archivist and had a countless number of albums and envelopes full of family photos but not many of her own family. Most likely, many of her photos were lost during the war. She held on to her family photos most of her life but as she grew older, she started to divide them up amongst her children. We discovered more photos after she passed away but not many more. QUESTION: Were there things you learned about yourself in writing this book? Yes, I would say that working on this project has made me realize the depth of my love for my Mom. It was hard to let go of her. QUESTION: If you were to do it over, what would you do differently. If I could do it over, I would have definitely started years earlier! I actually got to meet and spend time with Mom's brothers, Sadakazu and Tadashi, years ago in Japan when I was teaching English there. I saw them again later when my family and I visited Japan together. Looking back on it now, it would have been the perfect opportunity to interview them as Mom could have translated both ways. I wish I had thought of it then as all three are now gone. How did your mother’s retelling of the stories (both with auntie but also the other memories) match with your impressions of your uncles? How would you describe them? Mom's memories definitely matched up with my impressions of both Sadakazu and Tadashi. By the time my sister and I had met our uncles in Japan, they were both quite elderly but went out of their way to show us around and make sure we were well cared for. Sadakazu was outgoing and spoke in English as much as possible. He dressed formally most of the time (suit and tie) unless it was cold in which case he would wear a sweater and coat. Sadakazu loved to talk and ask questions and explain things. We ended up visiting all sorts of places with him: Akihabara, the electronics district; Shinjuku, where he had an office; Harajuku, which is famous for its youth culture; and various temples and shrines. We even got to see a couple of his favorite karaoke bars where he was a regular. While he sipped his usual sake, we would sing Frank Sinatra songs for him. Sadakazu also took us to visit our great-grandmother's grave which was located in a small cemetery in Tokyo behind an office building. There was a wooden bucket of water beside her headstone and he showed us how to ladle water on the stone to rinse it clean. His manner of speech could be a bit gruff but he also had a lot of humor about him. My sister and I loved Sadakazu's use of English: when exiting a taxi or building, he would say, "Okay, get out," instead of "Let's go." He was fond of saying "too much," when he meant to convey something more along the lines of "a lot." He called my sister "Baby" because she was the youngest of Mom's kids. His English sayings were both hilarious and adorable and it made us laugh every time. Tadashi was a little more quiet and reserved and relied upon his children to translate information back and forth. We spent a lot of time at his home with his family and also did some sightseeing around the area where he lived. We visited a castle that had aninja museum inside and went to see an evening fireworks show near a river. Tadashi's wife frequently hung onto his arm to support him as we walked around town because although he looked healthy, he was apparently frail. He dressed more casually than Sadakzau and was always offering us something to eat. He had a seemingly endless supply of snacks around the house and would pile them up on the table, encouraging us to eat more. Tadashi smiled often and had an air of relaxed contentment about him. Knowing now what he had been through with Auntie, my impression is that he had moved on from it and was someone who enjoyed life. I loved Sadakazu and Tadashi and miss them both tremendously. What was the birth order of your mom and her brothers? Sadakzu was the oldest, followed by Tadashi. Mom was the youngest child. QUESTION: Where can readers find you book? Forged in Fire is available to read for free on Wattpad.com. An illustrated print version of it is available on Amazon. I must mention that the print version was self-published and has three minor errors in it which have been noted on the Amazon site. A revised (corrected), illustrated e-book version is also available for iBooks (iTunes), Kindle (Amazon), Kobo (Kobo), NOOK (Barnes and Noble) and other types of e-pub readers (Smashwords). Publishing Forged in Fire on Wattpad has put me in touch with an amazingly supportive community of readers and writers (like you!) who have brought a whole other dimension to the project. I have such gratitude for their kindness and interest. Thank you so much for reaching out to me, Donna. I greatly appreciate the opportunity to have Mom's story featured! Photographic InterviewBecause Alexia's book is about family, memories, and wartime losses I wanted to use an interview strategy that would allow us into her world as a writer and as a daughter. I asked Alexia to select pictures or take photographs of family artifacts and share a little bit about them. She selected several meaningful items and told me why they were important to her. This English edition of Rashomon was a gift from my Mom to my Dad and was later given to me by Mom after Dad had passed away. The painted, wooden kokeshi dolls featured with the book's cover, belonged to Mom. Kokeshi are wooden dolls with moveable heads. Mom owned several pairs of kokeshi which were divided amongst my siblings and myself after she passed away. I included an image of the inside of the book along with a kokeshi-styled pencil topper that Mom gave to me when I was a kid. I wanted to share these images because Rashomon is a Japanese classic as are kokeshi, which are mentioned in Forged in Fire.  These two dolls are part of a small collection of Japanese dolls that Mom gave to me while she was still alive. I grew up with these dolls as her collection was displayed throughout various rooms in our family home. Although I have no idea how old these two are, my guess is that they were made in the 1940s, possibly pre-World War II. Although half of the dolls in her collection are Japanese in style, I chose to share these two which display a Western-styled influence that was prevalent in Japan at the time. They look like characters out of the 1939 film, "Gone With The Wind." The lower half of their bodies are cone-shaped, cardboard bases covered in cotton fabric. Their heads, upper bodies and bendable arms are made of wire armatures covered in stuffed silk. Both have dresses made from chiffon with lace and ribbon trim. The larger doll which is less than 10" tall, has fabric flowers strapped to one wrist; the smaller doll is approximately 8 1/4" in height and carries a basket made from pipe cleaners that display a tiny bunch of fabric flowers. Both have hand-painted features and soft, yarn-like hair. The taller doll has a bright-red, felt hat pinned to her head; the smaller one wears a flower-print head scarf. Both dolls are bit stained and moth-eaten but generally in great shape considering their age and how far they have travelled. These represent a fraction of the many postcards I have collected while traveling in Japan. Most of the ones featured were purchased as souvenirs which exception of one that was a free advertisement picked up at a cafe. What I love about them is how they reflect both the ancient and modern aspects of Japanese culture. In Japan, there is a deep love of tradition as well as an enthusiasm for technology. This sampling of postcards shows Kiyomizu-dera Temple in Kyoto; Mount Fuji; cherry blossoms; ukiyo-e print images; the interior of a kabuki theater; a kabuki actor; night views of Tokyo; and Osamu Tezuka's iconic, post-WWII manga character, Astro Boy.   This picture of Mom as a young woman in Toyko is featured in Forged in Fire: Stories of wartime Japan. I chose this image because it's one of my favorites of her and I love the fact that there are cherry blossoms in the background. The hand-painted frame belonged to her and I've photographed the back of the frame as well because I find it interesting. The frame has a solid wood back board held in place with nail-secured latches. Its corners are reinforced with metal details and it sports a mysterious, butterfly-shaped object made of metal with two holes in it. Wire can be strung through the holes for hanging. The picture and frame were acquired after she had passed away.  This is a picture of the rough draft that was used for editing Forged in Fire. At the time, I didn't have a name for Mom's story so I referred to it the "Mom Project." There are hand-written notes scrawled in the margins where I had taken down additional information that came up during our phone calls. Mom's brother, Sadakazu, would send each of us a holiday card every year. This photo displays a sampling of the various cards and letters I had received from him. The cards always had beautiful images and were sometimes made from textured paper. The letter shown is one that he had written to me after Dad had passed away. I wanted to share some of Sadakazu's written correspondence because it shows how thoughtful and loving he was. Since Tadashi was not as skilled in English as Sadakazu, he would write long letters in Japanese exclusively to Mom. Twice a year, Tadashi would ship large care packages to us full of senbei (rice crackers),nori (seaweed), tea, dried fruit and other treats. It makes me happy to remember the close bond that my Mom and her brothers shared with each other. Book ExcerptAUDIO EXCERPT

from "Childhood," Forged in Fire: Stories of Wartime Japan by Rita Tomoko Montibon and Alexia Montibon-Larsson Read by Alexia Montibon-Larsson |

RandomEnjoy my random posts. These are pieces of writing that don't "fit" in any of the other categories or posts updating what's new in my world.

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed