|

The Story: In what would turn out to be a horrible mistake with tragic consequences, seventeen-year-old Tim Parsell holds up a Fotomat with a toy gun. The stunt had been a gag but the girl behind the counter thinks the gun is real and hands a small sum of cash over to Tim who takes it and walks home. Tim is arrested and booked for armed robbery. He is convicted and sentenced to up to 15 years in the Michigan prison system (he serves 4 years). It doesn’t matter that the gun was a toy, the employee thought it was real and believed she was in mortal danger so the charge of “armed robbery” stands. According to Michigan law Tim is an adult at 17. Tim is sent to an adult close-security prison (akin to maximum security with extended time outside of prison cells). He enters an alternate society behind locked cells, prison gates, and under the watch of armed guards. While the criminal justice system looms in the background, a large amorphous machine that is inconceivably powerful and fundamentally unjust, Parsell’s memoir centers on the lives and dynamics of the prisoners and life inside the prison. It is a terrifying world of hierarchy, inmate code and deception. New prisoners are known as fish and like other fish Tim enters prison life with little knowledge of the rules and how to survive. Something as innocent as accepting a cigarette from an inmate may be entrapment. On Tim’s first day in the general prison population, he is drawn into a deceitful plot by a group of men pretending to befriend him. He senses something is off in the way the ringleader speaks to him (in a sort of cunning charm and long, suggestive glances). The men offer Tim ‘spud juice’ (home made prison liquor), and he joins them in drinking. What Tim doesn’t know is that the drink is spiked with Thorazine, a heavy tranquillizer. The drug takes effect and Tim is brutally gang raped, unable to so much as call for help. The drug is paralyzing. Once the sexual assault ends, the perpetrators flip a coin to determine who will own Tim. There after he is the property of the coin-toss winner, a man known as Slide Step. Despite the conditional relationship between Tim and Slide Step, the two men share an intimate bond. In exchange for sexual relations Slide Step –an inmate with high respect and status amongst the other prisoners– protects Tim. The two develop a closeness and intimacy that would be hard to understand outside of the context of trauma and the terror of prison. Review: Parsell’s honest account of incarceration in the Michigan prison system centers on sexual violence, exploitation, prison hierarchy, and inmate code. Reading the book kept me emotionally engaged and often terrified for Tim. As I continued to read I didn’t know how he could possibly survive his remaining sentence. Even when his term was nearly over and he had only a year to go, I wondered how he would make it. The tension never let up. I was fearful that injustice would strike again and he would not be released. I was deeply saddened when Tim was transferred to a new facility and without the protection of Slide Step, he was gang raped a second time, more violently than the first. It was even more heartbreaking when word of Tim’s sexual assault spread through the prison and he was targeted further and subject to ongoing harassment. Throughout the story my thoughts returned to the fact that Tim was a seventeen year old boy who was raped and forced into sexual slavery for robbing a Fotomat with a toy gun. After reading the book I found out that Tim (T.J. Parsell) is a human rights activist and has spent several decades working to change the conditions for prisoners and to end prison rape. In his prisoner advocacy work, Parsell often states that he feels he deserved to be punished for his crime, but did not deserve to be brutally raped and exploited. It is admirable that he acknowledges the traumatic impact the robbery must have had on the sales woman. I agree with him. However, I couldn’t help but think of the things I myself had done as a teenager and the trouble that friends of mine had gotten into. Teenagers do stupid things sometimes. Tim got caught and injustice repeatedly intervened in his young life. I agree with a need for contrition for a stupid, hurtful act — but how can justice be reached in the context of a system that subjects teenagers (and sometimes children) to torture? Paresell continues to work towards changing the prison system and protecting prisoners from sexual violence. He bravely uses his own story to shine a light on the broken prison system and give voice to the many victims of prison rape. In his book Fish: A Memoir of a Boy in a Man’s Prison, Parsell gives an empowered voice and dignity to the many prisoners who have suffered rape and exploitation. He has also demonstrated the courage to forge a path for all of us who have experienced trauma and the re-traumatizing effects of societal shame and stigmatization. I deeply admire his talent, courage, and insight. Links about the book and the author Fish the Movie is in development: The author’s T.J. Parsell’s website: http://tjparsell.com/ Fish: A Memoir of a Boy in a Man’s Prison on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/Fish-Memoir-Boy-Mans-Prison/dp/0786720379 T.J. Parsell talks about prison reform:

0 Comments

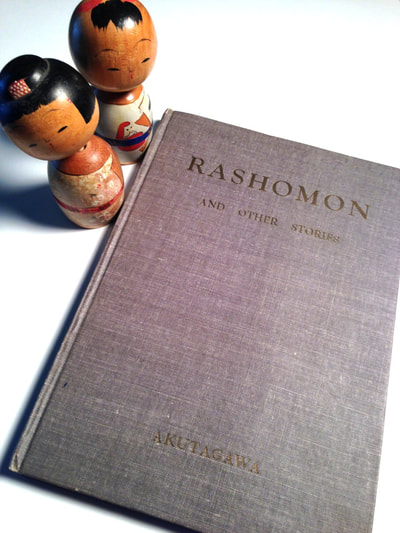

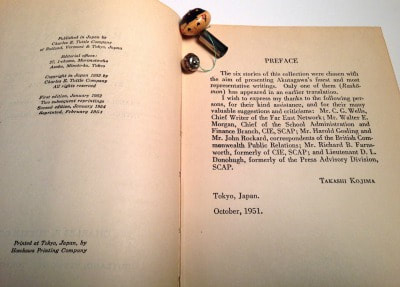

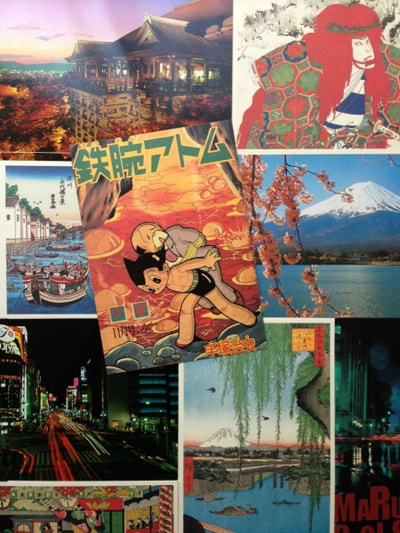

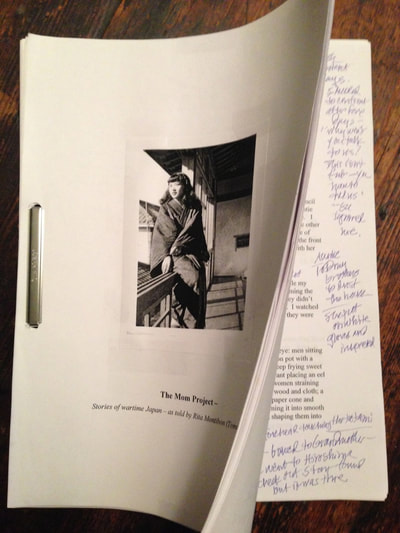

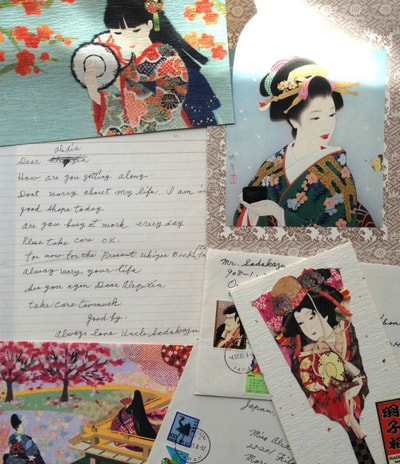

While browsing wattpad, I was fortunate to discover Alexia Montibon-Larsson’s book Forged In Fire: Stories of Wartime Japan. It is an elegant and lovingly rendered memoir / oral history. Montibon-Larsson skillfully captures her mother’s childhood experiences in occupied Japan following world war II . She reconstructs her mother’s memories in a historically accurate timeline. Montibon-Larsson’s meticulous attention to historical accuracy creates a dramatic tension throughout the story. We know the implications of escaping the desperate conditions in the city to go live with relatives an hour away from Hiroshima. Through her mother’s words,Montibon-Larsson presents a culturally authentic account of family life in occupied Japan. The prose is so lovely and well crafted, but it was also the intimacy between Montibon-Larsson and her mother (Rita Tomoko Montibon) that captivated me. Admittedly, at the end of the book I wanted more. It wasn’t that the story was incomplete, it was just so beautiful and welcoming I wanted to experience it a little longer. My interviews with Alexia Montibon-Larsson are presented in three parts (1) written responses to questions about her book and her writing process. (2) a commentary about several photographs of people or objects that have personal meaning and inspire her writing (3) an audio excerpt of her book Forged in Fire: Stories of Wartime Japan. After reading Alexia’s book, Forged in Fire: Stories of Wartime Japan, I wanted to find out more about her and the process of writing her book with her mother. We exchanged emails and started the interview process. Early on I asked her to answer a few questions about the stories and her process. The book was so well structured and developed. Her mother’s life stories followed a historical timeline. As I worked with Alexia more, I found out that there were many stages of interviewing, research, and writing. I loved the story but was also fascinated with the process of editing and synthesizing her mother’s recollections then presenting them in a historically accurate narrative. QUESTION: Can you talk a little about the book? Forged in Fire is the story of my mother’s childhood experiences before, during and after World War II in Tokyo and Kyushu, Japan. She was ten years old when the war started and fourteen years old when it came to an end. It recounts the hardships that she and her family endured and gives the reader a glimpse into what what life was like in Japan during those times. QUESTION: You must have heard many of your mom’s stories while you were growing up, what made you decide—at that point in time—to write a book about it? My Mom, along with my brother and his wife, had moved to New Mexico several years ago. My husband and I would travel to New Mexico once or twice a year to visit during summer and/or winter. Although my Mom was still fairly healthy, it was apparent to me with each visit that she was becoming more frail. Part of me knew that it was inevitable that we were going to lose her at some point and the knowledge of that impending loss pushed me to start the project. I knew it would be a daunting task which is probably why none of us (myself or my siblings) had yet gotten around to attempting the project. Mom and I worked on it together consistently over a period of approximately six months, up until a few weeks before she passed away. Of all of the children why do you think you were the one to do this project with your mom? That’s a good question because I’m not entirely sure of the answer. Although we all have busy lives, I may have been the first to initiate the project because I knew somehow that there wasn’t much time left and was driven to do one last thing for her: make her dream come true. How did your mom react when you asked her about doing the project? She was so excited about it. I’m sure she was thinking to herself: Finally! Where did you conduct the interviews? Over the phone or doing your visits? Initially, I conducted recordings at her home during visits. We would sit at her kitchen table and I would try to keep the conversation focused. We did about 2-3 of these sessions and after that everything else was done mainly over the phone. QUESTION: Can you talk a little bit about your process. How one would go about creating an oral history of a family member. My advice for creating an oral history of a family member is to collect as many stories as possible using whatever means are available or accessible: recordings; phone calls; photographs; documents; interviews with other family members, etc. Gathering as much information as possible in a short amount of time was the immediate goal. I had borrowed my husband’s digital recorder to tape a handful of conversations between myself and Mom during previous visits. After uploading the files into GarageBand (an Apple music editing application), I transcribed the recordings. It’s a time-consuming process that involves playing, stopping and replaying small snippets of audio at a time and writing everything down. To speed things up, I also wrote down the stories I already knew by heart in as much detail as I could remember. I would then call Mom with specific questions and we would have long conversations during which I would have my notes out so I could fill-in any gaps. These phone conversations inadvertently brought out more stories, some of which were new to me. As the writing progressed, I found myself frequently Google-searching details for clarification. For example, Mom had told me that she was pretty sure the name of the prison where the war criminals had been housed was called Sudamo prison. After fact-checking the name, I found that she had been close: it was actually called Sugamo, not Sudamo. That Mom had remembered as much about the name of a prison was amazing to me but normal for her. Her memory had always been sharp. If I had overlooked even the smallest detail of one of Mom’s stories — the color of some fabric trim or an ingredient in a dish — she was quick to point it out to me. I ended up with many pieces and fragments of her stories but needed to place them together in a way that would flow naturally. It then occurred to me create a timeline as a reference. I printed out the long, rambling documentation I had accumulated on my computer and cut it apart into paragraphs, spreading them across the living room carpet. Using the timeline, the pieces were moved into chronological order. Distinct sections were revealed: pre-war childhood; school memories; wartime; and the Occupation of Japan. Once a rough order had been determined, I taped all of the fragments onto pieces of paper and used them as a guide for editing. There was a lot of cutting and pasting that had to be done but it took shape quickly after that and the timeline itself became a part of the book. Did you prepare questions in advance. Your book is so rich with specific detail, what kinds of questions or prompts did you use with your mom to get her to open up and share so much? Initially, I hadn’t prepared any questions ahead of time. My mind was overwhelmed with all of the many stories she had shared with us throughout her lifetime and it was difficult to know where to begin. It started out along the lines of, Hey, Mom, remember how you used to tell us about how you would wander around the neighborhood and watch all of the shop keepers? She would say, “Oh, yeah,” and start recounting everything in great detail. I knew most of her stories well enough that I could start writing them down on my own. It was during the process of trying to connect the dots between stories that questions would start to form. For example, I was confused about her time in Kysuhu. When did that take place? For how long? Did the process change as it went on? The process changed slightly when Mom started calling with more details. As memories were triggered, she would leave messages: “Alexia, I remembered something else today. Call me back.” QUESTION: Were there unique challenges to conducting an oral history with a loved one? One of the unique challenges of conducting an oral history with a loved one is having to broach subjects or events which may be painful to that person. In this case, it involved discussing the death of Mom’s aunt. Growing up, I had heard all of the many wonderful stories of Auntie’s energy, modernity and creativity but could not recall a single story about how she had died. In order to complete the story, I was going to have to ask her about Auntie’s death. Obtaining this information from Mom brought out a whole new set of stories that included details how dead bodies were handled in Kyushu at the time. Talking about Auntie’s death unexpectedly triggered another wave of stories that revealed an abusive side of Auntie’s personality. This was a shock to me as well as Mom. It actually upset her quite a bit and she experienced feelings of guilt for not having been able to help her brother, Tadashi, who had suffered the most. To accomodate this new information, the book had to be re-edited to include a separate chapter, “Fairy Tale Witch.” Soon after, Mom called to request that Auntie be removed from the Dedication portion of the book and asked me to delete the sections that detailed Auntie’s abuse toward Tadashi. A week or so later, Mom changed her mind and said she was okay with keeping the details regrading the abuse in the story because it was the truth of what she and her brothers had gone though together. Did your mother express to you what it meant to be able to talk about these memories? Both with auntie and also the horrors of war? Had she shared these memories with anyone before you? Mom did tell me that she was glad I was recording her stories for her but didn’t express what it meant to talk about them. It occurred to me much later as an adult that the act of sharing her experiences had already been a form of therapy for her. As children, we knew the the horrors of her war experiences, mainly the ones about how she and her family starved; how her school was burned to the ground; how the sky turned blood red; how Sadakazu had to give up their heirlooms to survive. We also knew that Auntie was sometimes harsh. I was familiar with the story of Auntie hitting my Mom on the head with a pencil case but the more disturbing memories, like seeing a dead man lying next to a railroad track or witnessing Auntie kicking Tadashi were not shared until the project had been going on for some time. Mom had on rare occasion shared some of her stories with people outside of the family and was almost always encouraged to write a book. It was a lifelong desire for her to do so but she didn’t have the time or energy to actually go through with it. How did your siblings feel about these new insights into what your mother went through during the war? I think they were as surprised as I was about it, particularly the new stories about Auntie. QUESTION: Were there things you learned about your mother that you wouldn’t have expected? Yes, I learned much more about what drove Mom’s impulses, motivations and hopes for her family. Her wartime stories had always been a huge part of my own childhood experience but I gained additional insight into who she was as a person by writing them down. Everything she had seen, felt, lost and endured during the war years shaped who she became as an adult and as a mother. It explained a lot to me about her values; her devotion to American citizenship; and the fierceness of her love for us. QUESTION: Did your mother have any feelings about the US and the way Japanese Americans were treated here during WW2? I know she felt the forced internment of Japanese Americans was a sad and unjust act but she never spoke of U. S. wartime actions with anger or resentment. It was simply not part of her mindset. One of the stories she enjoyed recounting was how when she was interviewed for U. S. citizenship, she had been asked if she would be willing to die for her country and she had not hesitated to answer “Yes.” She felt becoming an American citizen was a great honor and privilege and she never took it for granted. QUESTION: How were the wartime stories a huge part of your childhood experiences? How she express these memories / experiences? Mom’s stories filled my imagination and I never grew tired of hearing them. Listening to her descriptions of people, places, food, dress styles, traditions and events, including wartime events, was a pleasure not just for me but my siblings as well. The feelings Mom had experienced came across in her storytelling: her curiosity; delight; excitement; frustration; sadness; despair. Her storytelling fueled my love for reading and the visual arts. QUESTION: Did your family keep albums or photographs of the places, people, in the book? Mom was the family archivist and had a countless number of albums and envelopes full of family photos but not many of her own family. Most likely, many of her photos were lost during the war. She held on to her family photos most of her life but as she grew older, she started to divide them up amongst her children. We discovered more photos after she passed away but not many more. QUESTION: Were there things you learned about yourself in writing this book? Yes, I would say that working on this project has made me realize the depth of my love for my Mom. It was hard to let go of her. QUESTION: If you were to do it over, what would you do differently. If I could do it over, I would have definitely started years earlier! I actually got to meet and spend time with Mom’s brothers, Sadakazu and Tadashi, years ago in Japan when I was teaching English there. I saw them again later when my family and I visited Japan together. Looking back on it now, it would have been the perfect opportunity to interview them as Mom could have translated both ways. I wish I had thought of it then as all three are now gone. How did your mother’s retelling of the stories (both with auntie but also the other memories) match with your impressions of your uncles? How would you describe them? Mom’s memories definitely matched up with my impressions of both Sadakazu and Tadashi. By the time my sister and I had met our uncles in Japan, they were both quite elderly but went out of their way to show us around and make sure we were well cared for. Sadakazu was outgoing and spoke in English as much as possible. He dressed formally most of the time (suit and tie) unless it was cold in which case he would wear a sweater and coat. Sadakazu loved to talk and ask questions and explain things. We ended up visiting all sorts of places with him: Akihabara, the electronics district; Shinjuku, where he had an office; Harajuku, which is famous for its youth culture; and various temples and shrines. We even got to see a couple of his favorite karaoke bars where he was a regular. While he sipped his usual sake, we would sing Frank Sinatra songs for him. Sadakazu also took us to visit our great-grandmother’s grave which was located in a small cemetery in Tokyo behind an office building. There was a wooden bucket of water beside her headstone and he showed us how to ladle water on the stone to rinse it clean. His manner of speech could be a bit gruff but he also had a lot of humor about him. My sister and I loved Sadakazu’s use of English: when exiting a taxi or building, he would say, “Okay, get out,” instead of “Let’s go.” He was fond of saying “too much,” when he meant to convey something more along the lines of “a lot.” He called my sister “Baby” because she was the youngest of Mom’s kids. His English sayings were both hilarious and adorable and it made us laugh every time. Tadashi was a little more quiet and reserved and relied upon his children to translate information back and forth. We spent a lot of time at his home with his family and also did some sightseeing around the area where he lived. We visited a castle that had aninja museum inside and went to see an evening fireworks show near a river. Tadashi’s wife frequently hung onto his arm to support him as we walked around town because although he looked healthy, he was apparently frail. He dressed more casually than Sadakzau and was always offering us something to eat. He had a seemingly endless supply of snacks around the house and would pile them up on the table, encouraging us to eat more. Tadashi smiled often and had an air of relaxed contentment about him. Knowing now what he had been through with Auntie, my impression is that he had moved on from it and was someone who enjoyed life. I loved Sadakazu and Tadashi and miss them both tremendously. What was the birth order of your mom and her brothers? Sadakzu was the oldest, followed by Tadashi. Mom was the youngest child. QUESTION: Where can readers find you book? Forged in Fire is available to read for free on Wattpad.com. An illustrated print version of it is available on Amazon. I must mention that the print version was self-published and has three minor errors in it which have been noted on the Amazon site. A revised (corrected), illustrated e-book version is also available for iBooks (iTunes), Kindle (Amazon), Kobo (Kobo), NOOK (Barnes and Noble) and other types of e-pub readers (Smashwords). Publishing Forged in Fire on Wattpad has put me in touch with an amazingly supportive community of readers and writers (like you!) who have brought a whole other dimension to the project. I have such gratitude for their kindness and interest. Thank you so much for reaching out to me, Donna. I greatly appreciate the opportunity to have Mom’s story featured! Because Alexia’s book is about family, memories, and wartime losses I wanted to use an interview strategy that would allow us into her world as a writer and as a daughter. I asked Alexia to select pictures or take photographs of family artifacts and share a little bit about them. She selected several meaningful items and told me why they were important to her. Rashomon book and kokeshi dolls This English edition of Rashomon was a gift from my Mom to my Dad and was later given to me by Mom after Dad had passed away. The painted, wooden kokeshi dolls featured with the book’s cover, belonged to Mom. Kokeshi are wooden dolls with moveable heads. Mom owned several pairs of kokeshi which were divided amongst my siblings and myself after she passed away. I included an image of the inside of the book along with a kokeshi-styled pencil topper that Mom gave to me when I was a kid. I wanted to share these images because Rashomon is a Japanese classic as are kokeshi, which are mentioned in Forged in Fire. Japanese Dolls These two dolls are part of a small collection of Japanese dolls that Mom gave to me while she was still alive. I grew up with these dolls as her collection was displayed throughout various rooms in our family home. Although I have no idea how old these two are, my guess is that they were made in the 1940s, possibly pre-World War II. Although half of the dolls in her collection are Japanese in style, I chose to share these two which display a Western-styled influence that was prevalent in Japan at the time. They look like characters out of the 1939 film, “Gone With The Wind.” The lower half of their bodies are cone-shaped, cardboard bases covered in cotton fabric. Their heads, upper bodies and bendable arms are made of wire armatures covered in stuffed silk. Both have dresses made from chiffon with lace and ribbon trim. The larger doll which is less than 10″ tall, has fabric flowers strapped to one wrist; the smaller doll is approximately 8 1/4″ in height and carries a basket made from pipe cleaners that display a tiny bunch of fabric flowers. Both have hand-painted features and soft, yarn-like hair. The taller doll has a bright-red, felt hat pinned to her head; the smaller one wears a flower-print head scarf. Both dolls are bit stained and moth-eaten but generally in great shape considering their age and how far they have travelled. Japanese Postcards These represent a fraction of the many postcards I have collected while traveling in Japan. Most of the ones featured were purchased as souvenirs which exception of one that was a free advertisement picked up at a cafe. What I love about them is how they reflect both the ancient and modern aspects of Japanese culture. In Japan, there is a deep love of tradition as well as an enthusiasm for technology. This sampling of postcards shows Kiyomizu-dera Temple in Kyoto; Mount Fuji; cherry blossoms; ukiyo-e print images; the interior of a kabuki theater; a kabuki actor; night views of Tokyo; and Osamu Tezuka’s iconic, post-WWII manga character, Astro Boy. Mom Portrait This picture of Mom as a young woman in Toyko is featured in Forged in Fire: Stories of wartime Japan. I chose this image because it’s one of my favorites of her and I love the fact that there are cherry blossoms in the background. The hand-painted frame belonged to her and I’ve photographed the back of the frame as well because I find it interesting. The frame has a solid wood back board held in place with nail-secured latches. Its corners are reinforced with metal details and it sports a mysterious, butterfly-shaped object made of metal with two holes in it. Wire can be strung through the holes for hanging. The picture and frame were acquired after she had passed away. Mom Project This is a picture of the rough draft that was used for editing Forged in Fire. At the time, I didn’t have a name for Mom’s story so I referred to it the “Mom Project.” There are hand-written notes scrawled in the margins where I had taken down additional information that came up during our phone calls. Sadakazu Cards Mom’s brother, Sadakazu, would send each of us a holiday card every year. This photo displays a sampling of the various cards and letters I had received from him. The cards always had beautiful images and were sometimes made from textured paper. The letter shown is one that he had written to me after Dad had passed away. I wanted to share some of Sadakazu’s written correspondence because it shows how thoughtful and loving he was. Since Tadashi was not as skilled in English as Sadakazu, he would write long letters in Japanese exclusively to Mom. Twice a year, Tadashi would ship large care packages to us full of senbei (rice crackers),nori (seaweed), tea, dried fruit and other treats. It makes me happy to remember the close bond that my Mom and her brothers shared with each other. AUDIO EXCERPT (scroll to bottom of page) from “Childhood,” Forged in Fire: Stories of Wartime Japan by Rita Tomoko Montibon and Alexia Montibon-Larsson Read by Alexia Montibon-L arsson The Sum of My Father's Life was originally published on Words and Pictures at rosegluckwriter.wordpress.com  I always knew my father left home sometime after high school –maybe 1959 or 1960 — and joined the army. A silence surrounded my father and his life was a hidden mystery. Like everything else he didn’t have a version of his experiences in the army. So I have to piece together his military years with scant evidence. Since there was still a military draft until Nixon ended it in 1968 and my father didn’t attend college after high school (that I know of) then he was likely drafted into the military. He never shared any stories about his experiences in the army except a little joke he would tell me when I sat on his lap as a young girl. He had a chicken pock scar on his forehead. I would touch it and ask him what it was. It was a clean edged pinhole. He said he was shot in the army. I knew it was a joke. I was surprised to read my father’s obituary in 1994 —penned by his second wife after my siblings and I were written out of my dad’s will and barred from attending the funeral by my stepmother and my nana. In his wife’s version, my father was a war hero. A war hero? This last biography of my father was a question mark to me, an irony, a contradiction. The father I knew was left winged, liked protest music of the 1960s. Later he idealized vigilantes and by the 1970s loved the monkey wrench gang. It was one of his identifications that were most salient to me, so different from my take on things. He loved the idea of dismantling telephone and electric poles, bringing down large looming institutions. Perhaps my dad dreamed of a version of himself as one of the misfits turned saboteurs: a monkey wrench gang member want to be. Once we’d moved to New Bedford Massachusetts, he settled into the job he would hold until he died in 1994 (a chemist with Titlest golf company), my father talked about encouraging the factory workers into revolt. Whether he actually ignited rebellious passions in the line workers I didn’t know but it seemed cowardly to me. I regretted feeling he was weak because he himself wouldn’t stand up for his beliefs. Instead he set up the vulnerable ones with the most to lose. He set up practical jokes and left me to take the heat. One time my born-again Christian cousins had given me a cassette tape of religious music they thought I would like. Really they knew I wouldn’t like it but perhaps they hoped that some of the Holy Spirit’s power would seep out of the lyrics and whip me into shape. Submissiveness or subservience or what ever they thought would save the soul of a girl like me. There we sat my father and I. I was nineteen at the time and he was laughing so hard he could hardly contain it. He knew how to fix a cassette so you could dub in other music. He taped over parts of the cassette with Billy Joel’s Only the Good Die Young “You didn’t count on me, when you were counting on your rosary.” I didn’t think it was as funny as he did. Particularly since I would be the one blamed. Either they would think I dubbed it myself just to mock them or they would think somehow the tape was infected by the demons they were trying to exorcise from me. I don’t know where I got this idea or this feeling that my dad was a coward. Perhaps it was years of being bullied by his father. Maybe he carried that fear with him. My whole life my father seemed seething and repressed. Unless he was intoxicated in someway, he was sheepish, not wanting to be seen. He cringed when he had to ask for assistance in a department store. Yet at home his feelings of inadequacy and powerlessness, held in over days or weeks erupted in violence. Sometimes destruction of property: holes in our doors when we had locked ourselves in the bathroom or bedrooms to keep him out. Fist holes my mother had my sister cover with drawings or felt decorations, glued to the wall. Conspicuous flowers or stars covering the evidence of my father’s rage. How childish those must have looked. So I wondered about the army. How had my father come to join the army? But, as I write this I can see that he wouldn’t have joined. He would have been drafted. The selective service was still active in the late 1950s. I can’t imagine him as a skinny teenager in a uniform. There isn’t one photograph of him as an enlisted man. I am weaving together pieces of his time in the army as I would imagine them and based on the little information I have, mostly from my mother. It would have been 1958 or 1959. Once drafted, men had a 2 year commitment to serve their country. This was after the Korean war and just before the Vietnam war. So, my father lucked out. He was called to serve his time in that safe reprieve. He would never have survived Vietnam. If anyone was ill equipped to deal with that sort of psychological and physical trauma I can say it was not my father. Very often he hid from things, cowered. Often when he and I were alone together he would weep. I was his confidant and many times I comforted him through tears. I learned more about my father than he ever told me in his obituary. I didn’t write it. His second wife Maria did with the help of my father’s bitter mother. The man Maria described was a stranger to me. It occurred to me that she constructed a story for him, his life story. Maybe she was trying to erase the weakness he couldn’t conceal. According to Maria: Paul Alan Barrow 54, died Saturday Feb. 5, 1994, after a long battle with brain cancer. He was the husband of Maria (Escobar) Barrow and son of Mary (Sharpe) Barrow of New Bedford and the son of the late William Barrow. He was born in New Bedford and was a resident of Fairhaven for the past eight years. He was employed at Titlist and Foot-Joy World-wide as a Senior Process Engineer for 21 years. Mr. Barrow served in the U.S. Army from 1959 to 1962, where he earned the Marksman Badge, the Sharpshooter Badge and the Driver-W Badge. He graduated from Dartmouth High School and Southeastern Mass. University, now UMass Dartmouth. He taught science at Case High School in Swansea, prior to joining Titlest.Survivors include his widow; his mother, a son P. Scott Barrow of San Francisco; two daughters Donna Barrow and Teresa Barrow both of San Francisco; a stepson, William Mitchell of Rochester; two brothers Robert Barrow of Falmouth and Raymond Barrow of Greenville R.I.; a sister Judith Ladino of New Bedford and several nieces and nephews. Arrangements are by the Fairlawn Mortuary, 180 Washington St. Fairhaven. I knew my father had served in the army but I — for some reason (likely from my mother) — thought it had been for a year not two. Likely he enlisted after his eighteenth birthday on November 23, 1957. He was likely called to serve sometime in 1958. Maybe he went through basic training. Then he was stationed in the south. My mother said she and my father met in TexArkana. There was a military base 18 miles west of TexArkana, the Red River Army Depot. In her memoir Farrago, Diana Roberts describes living near the base: The U.S. Army placed the apartment complex just outside TexArkana Proper which I understand is a very proper town. Everywhere there was dust and dry wind. No grass grew outside our apartment. Just dried mud. And when it rained which was not often my feet sank heavily into the mud…and there were tornadoes…and swarms of locusts in the summer… The Red River Army Depot was established during world war II as an ammunition depot and expanded after the war to warehouse general military supplies. It also had a combat vehicle repair complex, a training center. By the late 1950s when my father was stationed there it became a major guided missile maintenance and assembly center. Perhaps my father was sent to Red River Depot because of his affinity for engineering and science or maybe it was the other way around. Maybe his military work gave him the experience he would later use as a chemical engineer for Titlest. I have conflicting stories about my father the army man. My mother always told me that she met my father in a bar outside the military base where he was stationed. My mother’s account was that my father hated the army and was kicked out for being drunk, he received a dishonorable discharge –according to my mother. My account was, or rather my impression was that my father disliked authority and the government in particular. He was not necessarily disciplined or orderly. He wasn’t messy but he didn’t strike me as having the tendency towards order and routine that a military man would. My father woke up late, angry. He was particularly irritable in the mornings when my sister and I had school, waking us up shouting “get the Fuck up or you’ll miss the bus!” He was a fumer and mornings were particularly bad. My father also leaned towards hippie. He drank, smoked pot, and did a lot of drugs during my adolescent years. In sum, I never got the impression he was a military man and so my mother’s version of his career in the army went unquestioned until I read the obituary my father’s wife Maria wrote. The man she described in the obituary I had never met. I’d never once heard of any of the badges she mentioned. I was certain that my father would not have wanted to memorialized as dedicated employee of a corporation, and a loyal soldier. I believe my father would have wanted something more in line with Vonnegut or maybe even be memorialized through a story like Jonny Got his Gun, one of my father’s favorites. When my father was in his forties he discovered Joseph Campbell and Robert Bly the poet, anti-Vietnam activist, and founder of the mythopoet men’s movement. My father’s obituary would have been his last chance to release the sardonic alter self that he seemed to hide so well. If his wife was going to lie why didn’t she create the man he wanted to be rather than the man she wished she’d married. But maybe by then, by 9:40 on Saturday February 5, 1994, the moment he died he was so sick and so tired that there was nothing left. What are these badges his wife spoke of in his obituary? Certainly they might tell me something about what he did while in the military. I did a little research and found out the Marksman Badge is a badge a soldier receives for successful completion of a weapons qualification course or a weapons competition. The Sharp Shooter Badge is qualification for using weapons at a more proficient level. The army weapon badge grades range from lowest to highest (marksman, sharpshooter, and expert). The Driver –W badge is awarded for a high degree of skill in the operation and maintenance of wheeled motor vehicles. Wheeled military vehicles include jeeps, trucks, armored trucks, ambulance, wrecker, amphibious vehicles, and motorcycle. The Driver-W badge would not have qualified my father to work on tracked vehicles like tanks, artillery vehicles, or on airplanes. Am I cruel to feel pity for my father because his obituary highlighted that he was simply trained how to use a weapon and repair a truck in the army in 1958? Instead of medals he had badges that described training, some of which a civilian could have earned (Marksman). Twenty four of those 179 words that summarized his life in his obituary — the last word on who my father was — recounted facts he’d never told me my entire life? If my father had been so proud of his work in the military why had he never spoken of it? Instead of building war machines he reveled in the fantasy of dismantling the establishment’s infrastructure. He dreamed of being Edward Abbey not a veteran like his father. I feel bad looking at the photograph of my father associated with the obituary. The only thing I can say is “Dad why didn’t you ever tell anyone who you were? Now it’s too late. Now you are dead and everyone thinks either you felt pride over these inconsequential badges or maybe they think your wife is stupid for believing they were medals.” Or maybe the badges meant something to my dad. Some secret his wife kept and together they decided to put it up front and center. If you analyzed his obituary according to things of importance to him it would go like this (1) Husband to Maria would be first. (2) Then son to his mother Mary. (3) Next would be his position as process engineer at Titlest Golf Ball. (4) Then his military experience and the badges he won. (5) His education follows. (5) Then right down below at the bottom, almost as insignificant as can be are his three children. They are listed as survivors. And we were. _____________________ The Sum of My Father’s Life is an excerpted chapter from the forthcoming memoir Dad written by Donna Barrow-Green (Rose Gluck). You can find more of Donna Barrow-Green’s work on donnabarrowgreen.com |

RandomEnjoy my random posts. These are pieces of writing that don't "fit" in any of the other categories or posts updating what's new in my world.

Archives

August 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed